While over 90% of people experience a major traumatic event at some point during their lifetime, most walk away unscathed. Others, however, carry emotional scars for decades.

By BRIAN BLUMAUGUST

COVID-19 is back. It seems like everyone I know has been exposed or infected this summer. That includes me.

My latest bout with COVID stemmed from the same source as last time: not an unmasked ride on public transportation or a crowded party, but my kids.

Our daughter, Merav, was at our house with our seven-month-old granddaughter, Roni, when Merav started to spike a fever. She hoped it was just dehydration – it had been unbearably hot for weeks – but just to be safe, she took one of our home COVID tests.

It was positive.

A few hours later, so was Roni.

Merav was bummed but not panicked. These days, she said with an air of confident nonchalance, COVID is just like a bad flu or cold. There are no rules anymore on quarantine or distancing. Most people don’t even bother to test at home. Israel has shut down the once ubiquitous PCR drive-through testing stations

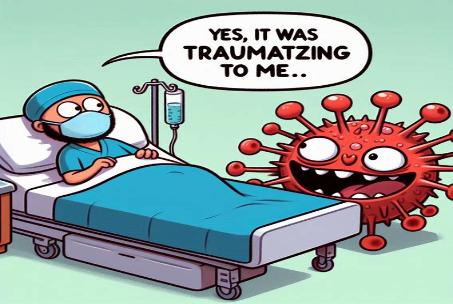

The story is very different for people with PTCD – post-traumatic COVID disorder. That’s not a real diagnosis in the DSM-5 [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition], but a strong correlation between PTSD and COVID has been documented, although it mainly refers to people who either were hospitalized with or are suffering from long COVID (with which an estimated 17.6 million Americans are now living, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

“Studies show that the experience of being hospitalized [with COVID] – being confused and frightened and feeling like you’re drowning – is traumatizing,” explains Cedars-Sinai psychiatrist Dr. Itai Danovitch. Up to a third of such patients develop PTSD.

To put that in perspective, while over 90% of people experience a major traumatic event at some point during their lifetime, Danovitch notes, most walk away unscathed. Others, however, carry emotional scars for decades.

It’s not just for serious cases.

When I contracted COVID for the first time two years ago, it was relatively mild. But I am still triggered by even the slightest possible exposure.

That’s not surprising. When COVID first burst onto the scene, no one knew much about the disease other than it was felling tens of thousands a week worldwide, eventually infecting 700 million people and killing seven million.

In those early days, there were no vaccines and few effective treatments. OG COVID was also more virulent than today’s super-contagious but relatively benign omicron subvariants. The rolling lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 further exacerbated the collective freak-out.

And then there’s the cancer factor: The patients who have the most life-threatening COVID outcomes remain the elderly and the immuno-compromised. While I don’t yet fit the first category, I am very much in the second due to chemo and other treatments I’ve had over the years. Put it all together and, voilà, it’s PTCD for me.

“I’m not sure if I’d use the word ‘trauma,’” a friend shares with me. However, after someone she was close with who was undergoing cancer treatment caught COVID and died, “I’m definitely taking it more seriously than before,” she says.

Another friend has essentially been bedridden with long COVID, suffering from kidney and heart problems. “COVID is not a cold. It’s not a flu. It’s a vascular/neurological illness similar to HIV. It’s insane to me that anyone would be nonchalant about getting or spreading COVID.”

An old college buddy concurred. “It affects every organ in your body in a way that makes you susceptible to more serious things like diabetes. The more you get COVID, the greater the risks for your body.”

“We still don’t know all of the things that COVID does, how it does it, and why,” notes Lara Jirmanus, a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. Not taking COVID seriously represents a kind of “hubris that almost assumes we can see the future.”

I WAS fortunate that this time around, my COVID was mostly mild again. I barely had a cough and had no fever. My nose was stuffy, and I had a nasty headache.

Which led to the next challenge for my PTCD: getting out of COVID.

How to recover from COVID

After a dozen or so days, I was starting to feel better – not perfect, but improved. So, I took a second home COVID test.

Still positive.

My wife, Jody, and I were invited to the wedding of the son of some of our closest friends the next night. I certainly didn’t want to be responsible for a super-spreader event.

The mother of the groom happens to be a doctor. So I asked her.

“I doubt you’re contagious after all this time,” she said, adding that the event will be outside, which should mitigate some of my concerns. “Please come. We couldn’t have a wedding without you guys there!”

Merav and Roni are fine now. Merav’s husband, Gabe, and our two-and-a-half-year-old grandson, Ilai, never got sick – or if they did, they were among the estimated one-third of people who catch COVID and are asymptomatic.

Another possibility: The journal Nature reported in June 2024 that some people may never catch COVID due to high levels of activity in a gene called HLA-DQA2.

As for me, at the three-week mark, I was still testing positive. My doctor told me to start with the antiviral Paxlovid, which had helped me last time. Even though Paxlovid is not supposed to be used after the first five days of symptoms, my hematologist said there’s anecdotal evidence it can work even when administered later.

“You can handle this,” Jody reassured me, repeating the mantra I’ve been working on lately.

The Paxlovid worked, thankfully; another five days and I was finally feeling fine. The entire experience was more annoyance than aggravation. Looking at it objectively and in hindsight, I can say it was far from traumatic.

No, I’m not about to throw caution entirely to the wind. But at the same time, I’m trying my hardest to not let PTCD lock me down again.