Authors: By: Neesha C. Siriwardane & Rodney Shackelford, DO, Ph.D. April 15, 2020

Introduction to COVID-19

Coronaviruses are enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses of the Coronaviridae family and order Nidovirales (1). The viruses are named for their “crown” of club-shaped S glycoprotein spikes, which surround the viruses and mediate viral attachment to host cell membranes (1-3). Coronaviruses are found in domestic and wild animals, and four coronaviruses commonly infect the human population, causing upper respiratory tract infections with mild common cold symptoms (1,4). Generally, animal coronaviruses do not spread within human populations, however rarely zoonotic coronaviruses evolve into strains that infect humans, often causing severe or fatal illnesses (4). Recently, three coronaviruses with zoonotic origins have entered the human population; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS) in 2003, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, and most recently, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), also termed SARS-CoV-2, which the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 31st, 2020 (4,5).

COVID19 Biology, Spread, and Origin

COVID-19 replicates within epithelial cells, where the COVID-19 S glycoprotein attaches to the ACE2 receptor on type 2 pneumocytes and ciliated bronchial epithelial cells of the lungs. Following this, the virus enters the cells and rapidly uses host cell biochemical pathways to replicate viral proteins and RNA, which assemble into viruses that in turn infect other cells (3,5,6). Following these cycles of replication and re-infection, the infected cells show cytopathic changes, followed by various degrees of pulmonary inflammation, changes in cytokine expression, and disease symptoms (5-7). The ACE2 receptor also occurs throughout most of the gastrointestinal tract and a recent analysis of stool samples from COVID-19 patients revealed that up to 50% of those infected with the virus have a COVID-19 enteric infection (8).

COVID-19 was first identified on December 31st, 2020 in Wuhan China, when twenty-seven patients presented with pneumonia of unknown cause. Some of the patients worked in the Hunan seafood market, which sold both live and recently slaughtered wild animals (4,9). Clusters of cases found in individuals in contact with the patients (family members and healthcare workers) indicated a human-to-human transmission pattern (9,10). Initial efforts to limit the spread of the virus were insufficient and the virus soon spread throughout China. Presently COVID-19 occurs in 175 countries, with 1,309,439 cases worldwide, with 72,638 deaths as of April 6th, 2020 (4). Presently, the most affected countries are the United States, Italy, Spain, and China, with the United States showing a rapid increase in cases, and as of April 6th, 2020 there are 351,890 COVID-19 infected, 10,377 dead, and 18,940 recovered (4). In the US the first case presented on January 19th, 2020, when an otherwise healthy 35-year-old man presented to an urgent care clinic in Washington State with a four-day history of a persistent dry cough and a two-day history of nausea and vomiting. The patient had a recent travel history to Wuhan, China. On January 20th, 2020 the patient tested positive for COVID-19. The patient developed pneumonia and pulmonary infiltrates, and was treated with supplemental oxygen, vancomycin, and remdesivir. By day eight of hospitalization, the patient showed significant improvement (11).

Sequence analyses of the COVID-19 genome revealed that it has a 96.2% similarity to a bat coronavirus collected in Yunnan province, China. These analyses furthermore showed no evidence that the virus is a laboratory construct (12-14). A recent sequence analysis also found that COVID-19 shows significant variations in its functional sites, and has evolved into two major types (termed L and S). The L type is more prevalent, is likely derived from the S type, and may be more aggressive and spread more easily (14,15).

Transmission

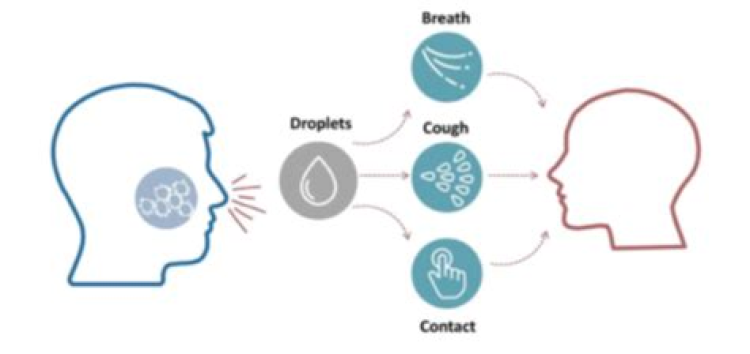

While sequence analyses strongly suggest an initial animal-to-human transmission, COVID-19 is now a human-to-human contact spread worldwide pandemic (4,9-11). Three main transmission routes are identified; 1) transmission by respiratory droplets, 2) contract transmission, and 3) aerosol transmission (16). Transmission by droplets occurs when respiratory droplets are expelled by an infected individual by coughing and are inhaled or ingested by individuals in relatively close proximity. Contact transmission occurs when respiratory droplets or secretions are deposited on a surface and another individual picks up the virus by touching the surface and transfers it to their face (nose, mouth, or eyes), propagating the infection. The exact time that COVID-19 remains infective on contaminated surfaces is unknown, although it may be up to several days (4,16). Aerosol transmission occurs when respiratory droplets from an infected individual mix with air and initiate an infection when inhaled (16). Transmission by respiratory droplets appears to be the most common mechanism for new infections and even normal breathing and speech can transmit the virus (4,16,17). The observation that COVID-19 can cause enteric infections also suggests that it may be spread by oral-fecal transmission; however, this has not been verified (8). A recent study has also demonstrated that about 30% of COIVID-19 patients present with diarrhea, with 20% having diarrhea as their first symptom. These patients are more likely to have COVID-19 positive stool upon testing and a longer, but less severe disease course (18). Recently possible COVID-19 transmission from mother to newborns (vertical transmission) has been documented. The significance of this in terms of newborn health and possible birth defects is currently unknown (19).

The basic reproductive number or R0, measures the expected number of cases generated by one infection case within a population where all the individuals can become infected. Any number over 1.0 means that the infection can propagate throughout a susceptible population (4). For COVID-19, this value appears to be between 2.2 and 4.6 (4,20,21). Unpublished studies have stated that the COVID10 R0 value may be as high as 6.6, however, these studies are still in peer review.

COVID-19 Prevention

There is no vaccine available to prevent COVID-19 infection, and thus prevention presently centers on limiting COVID-19 exposures as much as possible within the general population (22). Recommendations to reduce transmission within community include; 1) hand hygiene with simultaneous avoidance of touching the face, 2) respiratory hygiene, 3) utilizing personal protective equipment (PPE) such as facemasks, 4) disinfecting surfaces and objects that are frequently touched, and 5) limiting social contacts, especially with infected individuals (4,9,17,22). Hand hygiene includes frequent hand-washing with soap and water for twenty seconds, especially after contact with respiratory secretions produced by activities such as coughing or sneezing. When soap and water are unavailable, hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol is recommended (4,17,22). PPE such as N95 respirators are routinely used by healthcare workers during droplet precaution protocols when caring for patients with respiratory illnesses. One retrospective study done in Hunan, China demonstrated N95 masks were extremely efficient at preventing COVID-19 transfer from infected patients to healthcare workers (4,22-24). It is also likely that wearing some form of mask protection is useful to prevent COVID19 spread and is now recommended by the CDC (25).

Although transmission of COVID-19 is primarily through respiratory droplets, well-studied human coronaviruses such as HCoV, SARS, and MERS coronaviruses have been determined to remain infectious on inanimate surfaces at room temperature for up to nine days. They are less likely to persist for this amount of time at a temperature of 30°C or more (26). Therefore, contaminated surfaces can remain a potential source of transmission. The Environmental Protection Agency has produced a database of appropriate agents for COVID-19 disinfection (27). Limiting social contact usually has three levels; 1) isolating infected individuals from the non-infected, 2) isolating individuals who are likely to have been exposed to the disease from those not exposed, and 3) social distancing. The later includes community containment, were all individuals limit their social interactions by avoiding group gatherings, school closures, social distancing, workplace distancing, and staying at home (28,29). In an adapted influenza epidemic simulation model, comparing scenarios with no intervention to social distancing and estimated a reduction of the number of infections by 99.3% (28). In a similar study, social distancing was estimated to be able to reduce COVID-19 infections by 92% (29). Presently, these measured are being applied in many countries throughout the world and have been shown to be at least partially effective if given sufficient time (4,17,30). Such measures proved effective during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Singapore (30).

Symptoms, Clinical Findings, and Mortality

On average COVID-19 symptoms appear 5.2 days following exposure and death fourteen days later, with these time periods being shorter in individuals 70-years-old or older (31,32). People of any age can be infected with COVID-19, although infections are uncommon in children and most common between the ages of 30-65 years, with men more affected than women (32,33). The symptoms vary from asymptomatic/paucisymptomatic to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction, and death (4,9,32,33). The most common symptoms include a dry cough which can become productive as the illness progresses (76%), fever (98%), myalgia/fatigue (44%), dyspnea (55%), and pneumoniae (81%), with less common symptoms being headache, diarrhea (26%), and lymphopenia (44%) (4,32,33). Rare events such as COVID-19 acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy have been documented and one paper describes conjunctivitis, including conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, or increased secretions in 30% of COVID-19 patients (34,35). Interestingly, about 30-60% of those infected with COVID-19 also experience a loss of their ability to taste and smell (36).

The clinical features of COVID-19 include bilateral lung involvement showing patchy shadows or ground-glass opacities identified by chest X-ray or CT scanning (34). Patients can develop atypical pneumoniae with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (33). Additionally, elevations of aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine aminotransferase (41%), C-reactive protein (86%), serum ferritin (63%), and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, whose levels correlate positively with the severity of the symptoms (4,31-33,37-39).

About 81% of COVID-19 infections are mild and the patients make complete recoveries (38). Older patients and those with comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have a more difficult clinical course (31-33,37-39). In one study, 72% of patients requiring ICU treatment had some of these concurrent comorbidities (40). According to the WHO 14% of COVID-19 cases are severe and require hospitalization, 5% are very severe and will require ICU care and likely ventilation, and 4% will die (41). Severity will be increased by older age and comorbidities (4,40,41). If effective treatments and vaccines are not found, the pandemic may cause slightly less than one-half billion deaths, or 6% of the world’s population (41). Since many individuals infected with COVID-19 appear to show no symptoms, the actual mortality rate of COIVD-19 is likely much less than 4% (42). An accurate understanding of the typical clinical course and mortality rate of COVID-19 will require time and large scale testing.

COVID-19 Diagnosis

COVID-19 symptoms are nonspecific and a definitive diagnosis requires laboratory testing, combined with a thorough patient history. Two common molecular diagnostic methods for COVID-19 are real-time reverse polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and high-throughput whole-genome sequencing. RT-PCR is used more often as it is cost more effective, less complex, and has a short turnaround time. Blood and respiratory secretions are analyzed, with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid giving the best test results (43). Although the technique has worked on stool samples, as yet stool is less often tested (8,43). RT-PCR involves the isolation and purification of the COVID-19 RNA, followed by using an enzyme called “reverse transcriptase” to copy the viral RNA into DNA. The DNA is amplified through multiple rounds of PCR using viral nucleic acid-specific DNA primer sequences. Allowing in a short time the COVID-19 genome ti be amplified millions of times and then easily analyzed (43). RT-PCR COVID-19 testing is FDA approved and the testing volume in the US is rapidly increasing (44,45). The FDA has also recently approved a COVID-19 diagnostic test that detects anti-COVID-19 IgM and IgG antibodies in patient serum, plasma, or venipuncture whole blood (43). As anti-COVID-19 antibody formation takes time, so a negative result does not completely preclude a COVID-19 infection, especially early infections. Last, as COVID-19 often causes bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, correlating diagnostic testing results with lung chest CT or X-ray results can be helpful (4,31-33,37-39).

Testing for COVID-19 is based on a high clinical suspicion and current recommendations suggest testing patients with a fever and/or acute respiratory illness. These recommendations are categorized into priority levels, with high priority individuals being hospitalized patients and symptomatic healthcare facility workers. Low priority individuals include those with mild disease, asymptomatic healthcare workers, and symptomatic essential infrastructure workers. The latter group will receive testing as resources become available (41,46,47).

COVID-19 Possible Treatments

Presently research on possible COVIS-19 infection treatments and vaccines are underway (48). At the writing of this article many different drugs are being examined, however any data supporting the use of any specific drug treating COVID-19 is thin as best. A few drugs that might have promise are:

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine has been used to treat malarial infections for seventy years and in cell cultures it has anti-viral effects against COVID-19 (49). In one small non-randomized clinical trial in France, twenty individuals infected with COVID-19 who received hydroxychloroquine showed a reduced COVID-19 viral load, as measured on nasopharyngeal viral carriage, compared to untreated controls (50). Six individuals who also received azithromycin with hydroxychloroquine had their viral load lessened further (50). In one small study in China, a similar drug (chloroquine) was superior in reducing COVID-19 viral levels in treated individuals compared to untreated control individuals (51). These results are preliminary, but promising.

Remdesivir

Remdesivir is a drug that showed value in treating patients infected with SARS (52). COVID-19 and SARS show about 80% sequence similarity and since Remdesivir has been used to treat SARS, it might have value in treating COVID-19 (52). These trials are underway (48). Remdesivir was also used to treat the first case of COIVD-19 identified within the US (11). There are many other drugs being examined to treat COVID-19 infections, however, the data on all of them is presently slight to none, and research has only begun. There is an enormous research effort underway, and progress should be rapid (48).

Conclusion

Our understanding of COVID-19 is changing extremely rapidly and new findings come out daily. Combating COVID-19 effectively will require multiple steps; including slowing the spread of the virus through socially isolating and measures such as hand washing. The development of effective drug treatments and vaccines is already a priority and rapid progress is being made (48). Additionally, many areas of the world, such as South American and sub-Saharan Africa, will be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and are likely to have their economies and healthcare systems put under extreme stress. Dealing with the healthcare crisis in these countries will be very difficult. Lastly, several recent viral pandemics (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19) have come from areas where wildlife is regularly traded, butchered, and eaten in conditions that favor the spread of dangerous viruses between species, and eventually into human populations. The prevention of new viral pandemics will require improved handling of wild species, better separation of wild animals from domestic animals, and better regulated and lowered trade in wild animals, such as bats, which are known to be a risk for carrying potentially deadly viruses to human populations (53).

References

- Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:181-92.

- Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020;367:1260-3.

- Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020;367:1444-8.

- CDC. 2019 Novel coronavirus, Wuhan, China. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronvirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html. Accessed 6 April 2020.

- SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses.Nat Rev Microbiol 2016;14:523-34.

- Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:439-50.

- The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird’s Eye View. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020;11:65-71.

- Evidence for Gastrointestinal Infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology 2020;S0016-5085:30282-1.

- Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207.

- A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating a person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020;395:514-23.

- First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States.N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929-36.

- A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270-3.

- Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;79:104212.

- The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9.

- On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Natl Sci Review 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa036

- National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. Prevent guidelines of 2019-nCoV. 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202001/bc661e49bc487dba182f5c49ac445b.shtml. Accessed 6 April 2020.

- Transmission Potential of SARS-CoV-2 in Viral Shedding Observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446.

- Digestive symptoms in CVOID-19 patients with mild disease severity: Clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing, and outcomes. https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Documents/COVID19_Han_et_al_AJG_Preproof.pdf

- Neonatal Early-Onset Infection With SARS-CoV-2 in 33 Neonates Born to Mothers With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

- Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207.

- Data-based analysis, modelling and forecasting of the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230405.

- Covid-19 – Navigating the Uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1268-9.

- Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;S2213-2600(20)30134-X.

- Association between 2019-nCoV transmission and N95 respirator use. J Hosp Infect. 2020i:S0195-6701(20)30097-9.

- Recommendation Regarding the Use of Cloth Face Coverings, Especially in Areas of Significant Community-Based Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html.

- COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: estimating the epidemic potential and effectiveness of public health countermeasures. J Travel Med. 2020 Feb 28.

- https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2.

- Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;S1473-3099(20)30162-6.

- The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet, Public Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6.

- SARS in Singapore–key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006;35:301-6.

- Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-207.

- Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:441-7.

- Clinical features of patents infected with novel 2019 coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497-506.

- COVID-19-associated Acute Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Encephalopathy: CT and MRI Features. Radiology 2020:201187.

- Characteristics of Ocular Findings of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, ChinaJAMA Ophthalmol. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291.

- A New Symptom of COVID-19: Loss of Taste and Smell. 38. Obesity. 2020. doi: 10.1002/oby.22809.

- Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

- Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:507-13.

- The cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of severe COVID-19 and Interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) antagonist Tocilizumab may be the key to reduce the mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;28:105954.

- Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323:1061-9.

- Unknown unknowns – COVID-19 and potential global mortality. Early Hum Dev. 2020;144:105026.

- Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2). Science 2020 Mar 16. pii: eabb3221.

- Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCREuro Surveill. 2020;25. 44. https://www.fda.gov/media/136598/download

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136622/download

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluating and Testing Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. COVID-19 Prioritization of Diagnostic Testing. https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/public-health/covid-19-prioritization-of-dx-testing.pdf

- Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates. Science 2020:367;1412-3.

- Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 202018;6:16.

- Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020:105949.

- Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 2020;14(1):72-73.

- Remdesivir for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causing COVID-19: An evaluation of the evidence. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 2:101647.

- Permanently ban wildlife consumption. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/367/6485/1434.2.