- Darren Haywood, Susan L. Rossell & Nicolas H. Hart, BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 1230 (2025)

Abstract

Brain fog is a highly common condition that can have significant impacts on quality of life and functioning. Most people will experience a condition, illness, or infection that might result in the development of brain fog. We provide a call to action to minimise the impacts of brain fog.

Introduction

“Sorry, i’m feeling a little foggy today…”

The feeling of ‘brain fog’ is not uncommon [1], with more than a quarter of adults in the general population (28.2%) reporting experiencing it [1]. Brain fog can be reflected in many ways. Some days people might experience a slowing down of thoughts, trouble concentrating, a sense of confusion, or difficulties following conversations [1, 2]. Sometimes when people feel ’foggy’ they suggest potential causes, like consuming alcohol the night prior, or a lack of sleep [3]. While brain fog of this nature may last a few hours or a couple of days, for people experiencing brain fog as the result of other causes it can be a significantly debilitating condition that negatively impacts their lives and can last decades [4]. Long-term brain fog can also present episodically, with some experiencing periods of normal cognitive functioning disrupted by periods of significant brain fog that may last hours or days [1, 2]. Worryingly, the causes of long-term brain fog are not uncommon, thus it is probable that during our lives we will experience a condition, illness, or infection that might result in the development of longer-lasting brain fog [1, 3, 5].

In this Comment, we discuss what is known and not known about brain fog and demonstrate it as a significant global public health concern, while providing a call to action, including specific research directions, that are required to enhance our understanding, prevention, management, and treatment of brain fog globally.

What we know about brain fog

Brain fog is characterised by a slowing of thought and processing, difficulties remembering, slowing of responses, and communication difficulties, and is experienced across the population [1]. Particular subpopulations, such as people with long COVID-19, cancer, kidney dysfunction, HIV, hepatitis, fibromyalgia, pregnancy, or psychological challenges, often experience especially severe and long-lasting brain fog that might not remit [1, 3, 6, 7]. Brain fog has been acknowledged as a serious problem across these conditions for over two decades with exploratory research attempting to establish its causative mechanisms. While we are still improving our knowledge of brain fog’s aetiology, research within these vulnerable subpopulations points toward changes in factors like neuronal activity, inflammation, hormones, and nutritional deficiencies caused by their condition [8].

Brain fog can have a significant impact on people’s lives, including occupational functioning, relationships, psychological well-being, and performance of daily activities [1, 2]. This can result in not returning to work after an illness, missed days of work, poor productivity, and the inability to effectively care for children and support partners [2]. For example, people experiencing long-term brain fog may not feel confident returning to work due to their slower cognitive processing [2, 4] or have parental challenges [2, 4]. Lastly, brain fog often impacts self-perception, self-identify, and self-worth, leading to anxiety and depression [2, 4, 5].

Interventions seeking to improve cognitive dysfunction (‘brain fog’) continue to be studied, assessed, and developed [2]. There has been some success across these vulnerable subpopulations in reducing brain fog through non-pharmacological interventions such as physical activity or exercise, diet, cognitive rehabilitation (i.e., ‘brain training’), and psychological treatment [8,9,10], as well as pharmacological interventions [8]. However, treatments and supportive care strategies are far from consistently effective and are rarely implemented in clinical practice [9].

What we don’t know about brain fog

While we know brain fog is common and could be caused by a range of different factors, four important questions remain:

What is brain fog really?

Brain fog is commonly described across a variety of populations but what brain fog actually is remains unclear [3]. The experience of brain fog is often empirically captured via self-reported measures of perceived cognitive functioning, or sometimes supplemented by the use of objective measures of neuropsychological tests [1, 3]. These measures have historically assessed cognitive functioning generally (of which dysfunction is often characterised by brain fog), however there has been the recent development of a purpose-built self-report measure for brain fog specifically; called the Brain Fog Scale [11]. Problematically for clinicians and researchers, self-reported measures of perceived cognitive functioning do not strongly relate to its objective measures [12], apparent across populations. For example, some cancer survivors demonstrate cognitive impairments on self-report measures, but not objective measures, and others demonstrate the opposite [5, 8]. Therefore, whether brain fog is an objective cognitive dysfunction or something entirely different is not clear. Future co-design research with people who experience brain fog (from different conditions) and experts is required to develop a consistent definition.

Is brain fog the same ‘thing’ across all potential causes?

The experience of brain fog may have several different causes depending on the individual [1]. However, the reported experience of brain fog is remarkably similar across subpopulations (e.g., 2). It is unknown if brain fog, regardless of the cause, may be one consistent thing. This is important as it may suggest that there is potential for global, as well as specific, prevention, treatment, and supportive care approaches across subpopulations.

What can we do to prevent getting brain fog?

There is limited understanding about how we can prevent brain fog. There has been some progress in people with cancer and other subpopulations undergoing planned treatment for their condition [8]. Prehabilitation strategies using medication, more targeted treatments such as cognitive training, and lifestyle change show promise in minimising the anticipated occurrence and severity of brain fog [8]. However, for the broader population without planned treatments for a condition, empirically based approaches to prevent brain fog are limited.

If we do experience brain fog, what can we do about it?

While there has been some success in treating brain fog in specific subpopulations, strategies for minimising brain fog for the broader population are limited. Even the success of interventions for some sub-populations is variable and the lasting impact of the interventions on real-world functioning is questionable [13].

Brain fog as a significant global public health concern

For some, brain fog might last for a short period (e.g., a day or week), but for others, it can last decades [8]. While most available brain fog research is within subpopulations, brain fog is a broad and growing concern. In recent years, we have understood that COVID-19 infection can lead to experiencing brain fog [6], as one of the most commonly reported effects of acute and long-COVID [1, 6], and may last multiple years. With a significant proportion of the global population acquiring the COVID-19 infection, and approximately 62% experiencing long-COVID [6], brain fog is a global public health concern.

Beyond COVID, improvements to the treatment of conditions associated with increased risk of brain fog mean that more people with brain fog are living longer and require support. For example, the 5-year survival rate of cancer has significantly improved. In Australia, the 5-year survival rate for all cancer was 53% in the mid-1990s, and then 71% twenty years on [14]. Given that cancer and cancer treatments can cause brain fog in a significant number of cancer survivors, millions more people will experience lasting brain fog. This trend is similar for other conditions associated with brain fog, such as kidney disease [15].

We must urgently improve our understanding of brain fog and its management

Brain fog can have severe impacts on people’s lives and those close to them across various domains [2, 4], however changes to cognitive functioning (including for brain fog) are also related to the development of psychological disorders [5]. Therefore, given the rising number of people experiencing lasting brain fog globally, the condition has significant implications for (a) the global economy through missed days of work and healthcare costs, (b) the healthcare burden through increased comorbidities, treatment and supportive care needs, and (b) the quality of life of the person with brain fog and those close to them.

Call to action

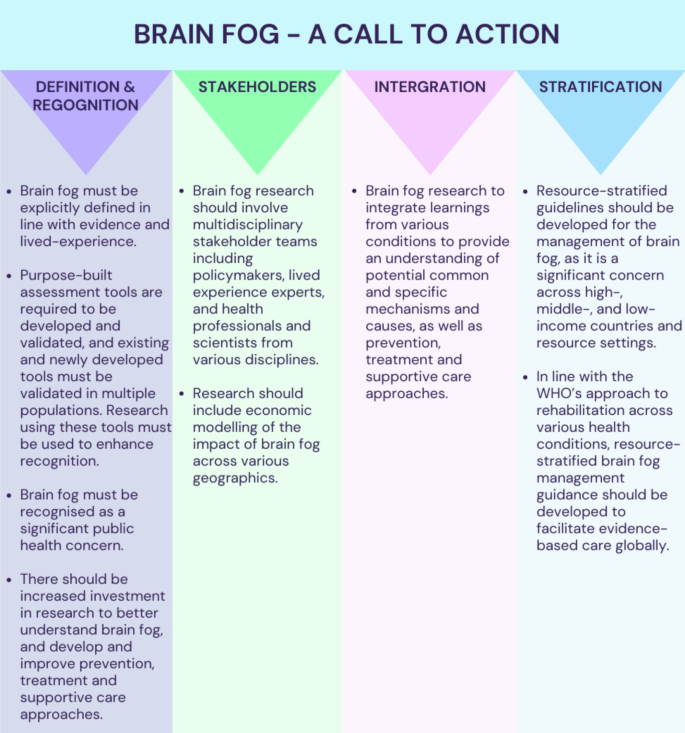

Below (in Fig. 1) we provide a call for urgent action to minimise brain fog and its consequences with the goal of ultimately minimising brain fog’s impact on global health, sociality, and economy.