Toka Elboraay, Mahmoud A. Ebada, Maged Elsayed, et. al., BMC Neurology volume 25, Article number: 250 (2025)

Abstract

Background

Neuropsychiatric symptoms emerged early in the COVID-19 pandemic as a key feature of the virus, with research confirming a range of neuropsychiatric manifestations linked to acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the persistence of neurological symptoms in the post-acute and chronic phases remains unclear. This meta-analysis assesses the long-term neurological effects of COVID-19 in recovered patients, providing insights for mental health service planning.

Methods

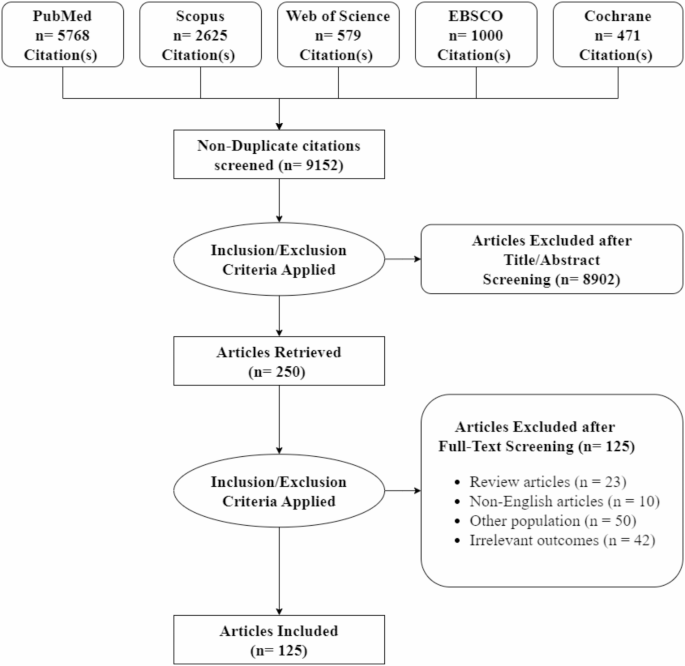

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across five electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO, and CENTRAL, up to March 22, 2024. Studies evaluating the prevalence of long-term neurological symptoms in COVID-19 survivors with at least six months of follow-up were included. Pooled prevalence estimates, subgroup analyses, and meta-regression were performed, and publication bias was assessed.

Results

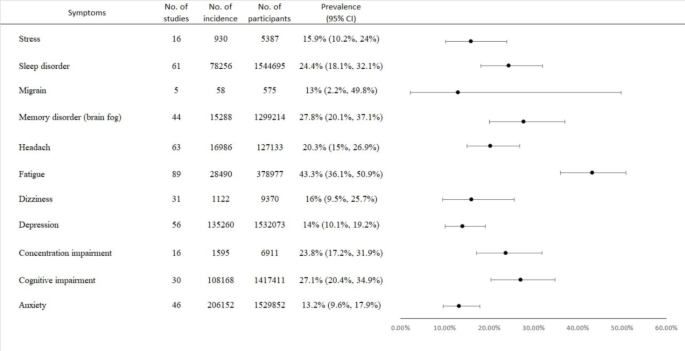

The prevalence rates for the different symptoms were as follows: fatigue 43.3% (95% CI [36.1-50.9%]), memory disorders 27.8% (95% CI [20.1-37.1%]), cognitive impairment 27.1% (95% CI [20.4-34.9%]), sleep disorders 24.4% (95% CI [18.1-32.1%]), concentration impairment 23.8% (95% CI [17.2-31.9%]), headache 20.3% (95% CI [15-26.9%]), dizziness 16% (95% CI [9.5-25.7%]), stress 15.9% (95% CI [10.2-24%]), depression 14.0% (95% CI [10.1-19.2%]), anxiety 13.2% (95% CI [9.6-17.9%]), and migraine 13% (95% CI [2.2-49.8%]). Significant heterogeneity was observed across all symptoms. Meta-regression analysis showed higher stress, fatigue, and headache in females, and increased stress and concentration impairment with higher BMI.

Conclusions

Neurological symptoms are common and persistent in COVID-19 survivors. This meta-analysis highlights the significant burden these symptoms place on individuals, emphasizing the need for well-resourced multidisciplinary healthcare services to support post-COVID recovery.

Registration and protocol

This meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD42024576237.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, driven by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has profoundly affected global health, transcending the acute respiratory symptoms typically associated with the infection [1,2,3]. Beyond the immediate respiratory challenges, a growing body of evidence has illuminated significant neurological and neuropsychiatric sequelae in individuals who have survived the acute phase of COVID-19 [4,5,6,7,8,9]. These sequelae encompass a diverse spectrum of symptoms that can persist long after the initial infection has resolved. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as “Long COVID” or “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection” (PASC), highlighting the multi-systemic nature of these persistent symptoms, which can impact various bodily systems, particularly the central nervous system [10,11,12].

The long-term neurological effects of COVID-19 present substantial public health concerns, as a variety of symptoms—including cognitive impairment, fatigue, sleep disturbances, persistent headaches, and mood disorders—can endure long after the initial infection has resolved [13,14,15,16,17]. This spectrum of symptoms affects individual wellbeing and has broader implications for healthcare systems and societal productivity. Notably, a study by Taquet et al. involving over 200,000 patients indicated that approximately 34% experienced cognitive deficits lasting beyond six months post-infection [18]. This highlights the substantial risk of long-term cognitive impairment among those who have recovered from COVID-19.

The potential mechanisms contributing to these enduring effects remain a topic of ongoing research. Hypotheses include direct viral invasion of the CNS, immune-mediated neuroinflammation, and vascular changes affecting cerebral circulation, which may impair cognitive and emotional functioning [19]. This complexity necessitates a nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving these long-term effects.

Despite the increasing volume of literature addressing these issues, significant gaps persist in understanding the prevalence, mechanisms, and longitudinal consequences of neurological complications following COVID-19. Such gaps highlight the urgent need for comprehensive assessments that can inform clinical practice and public health strategies to mitigate these effects. Understanding the long-term neurological outcomes of COVID-19 is crucial for developing targeted interventions that address both physical and mental health, ultimately improving the quality of life for affected individuals.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to investigate the long-term neurological effects in recovered COVID-19 patients, quantifying the range and frequency of symptoms to enhance clinical practice. The findings may offer valuable insights for mental health service planning, emphasizing the necessity for integrated care strategies that address both physical and psychological support to improve recovery outcomes for affected individuals.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [20] and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [21, 22]. This meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD42024576237.

Literature search strategy

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases for studies published in English assessing long-term neurological symptom prevalence among COVID survivors through March 22, 2024. The main search terms used were “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “2019-nCoV,” and “novel coronavirus” in conjunction with “neurological,” “brain,” “central nervous system,” “insomnia,” “sleeplessness,” “poor sleep,” “impaired sleep,” “lack of sleep,” “dizziness,” “cognitive impairment,” “stress,” “concentration impairments,” “memory problems,” “brain fog,” “fatigue,” “migraine,” “headache,” “depression,” and “anxiety,” in conjunction with “long-term” and “chronic.” Detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria

All studies that matched the following criteria were included: original research; follow-up at least six months post-recovery from COVID-19; and studies that assessed at least one of the following outcomes: long-term impact on dizziness, cognitive impairment, stress, concentration impairments, depression, memory problems (brain fog), fatigue, sleep, anxiety, migraine, and headache. Additionally, studies were included if they provided raw data that allowed for the calculation of estimates.

We excluded studies with incomplete or inexact quantitative data, meaning no exact proportions were provided for primary outcomes. Studies with outcomes that were present prior to COVID-19 exposure, follow-up times of less than six months since COVID-19 infection or diagnosis, post-mortem studies of COVID-19 patients, unpublished studies, conference abstracts, theses, case reports, studies with a sample size of fewer than 10 persons, or protocols were also excluded. Non-original articles were not considered.

Study selection

All articles were imported into Rayyan, and duplicates were removed using Endnote. The retrieved references were then screened in two stages: first, four authors (OR, ME, LE, and ME) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the identified articles to assess their relevance to the meta-analysis. In the second stage, the full-text articles of the selected abstracts were examined to determine their final eligibility for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The study supervisor (MAE) resolved any discrepancies.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using Excel software by four authors (OR, ME, LE, and ME) independently from the included studies, utilizing a standardized data extraction sheet. This sheet included key aspects such as the author, publication year, sample size, study location, study design, age, gender, race, follow-up period, body mass index, smoking history (categorized as non-smoker, former smoker, or active smoker), disease severity (ranging from community infection to hospitalization or ICU admission), and neurological outcomes (including sleep disorders, dizziness, stress, cognitive impairment, concentration impairment, memory disorders, headache, fatigue, migraine, depression, and anxiety). Any disagreements were resolved through a joint review with a fifth author (TE).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [23]. According to the NOS criteria, we assigned a maximum of four stars for selection bias, two stars for comparability evaluation, and three stars for exposure and outcome assessment. Studies were categorized based on their total star count: fewer than five stars indicated low quality; five to seven stars indicated moderate quality; and more than seven stars indicated high quality. Four investigators (OR, ME, LE, and ME) independently assessed each item on the scale. A fifth author (TE) facilitated a joint review to resolve any disagreements.

Data synthesis

Meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of each neurological sequela among COVID-19 survivors after hospital discharge. The I² index was calculated to assess between-study heterogeneity, and the Cochrane Q-test was used to determine statistical significance. An I² value greater than 50% or a chi-square p-value less than 0.05 indicated substantial heterogeneity. Pooled rates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using the random-effects model if heterogeneity was present; otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed on the estimated prevalence of symptoms, stratified by mean age of study participants, country, study design (retrospective, prospective, cross-sectional, ambispective), female proportion in the studies, follow-up duration (6–9 months, > 9 to 12 months, and > 12 months), and severity of acute COVID-19 infection (community patients, mild or moderate hospitalized patients, and patients admitted to intensive care). Funnel plots and Egger’s test were employed to assess publication bias. All analyses were conducted using R Software (version 4.0.3).

Results

Search results and characteristics of the included studies

A comprehensive literature search yielded 10,443 studies. After removing duplicates, 9,152 studies remained for screening. From these, 125 original articles [16, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147] met the eligibility criteria and were included in the quantitative synthesis, Fig. 1. The included studies, published between 2020 and 2024, involved a cumulative total of 4,045,211 participants across 33 countries. The included studies demonstrate significant geographic diversity and highlight various focus areas. The USA emerged as the most frequently mentioned country, appearing 25 times. Germany was next with 14 mentions, followed by Spain with 11. Italy was mentioned 9 times, China 8 times, and Brazil 6 times. Switzerland was noted 5 times. Iran, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the Netherlands, Sweden, and France each appeared 4 times. The UK, Mexico, Iraq, Israel, Finland, Egypt, and Austria were mentioned twice. Denmark, India, Russia, Canada, Pakistan, Ireland, Aruba, Portugal, Colombia, Norway, Indonesia, and Chile each had a single mention. The follow-up periods for the studies predominantly range from 6 to 12 months, with several studies extending to 24 and 48 months, indicating a commitment to long-term monitoring and evaluation of outcomes. A detailed summary of the included studies and their population characteristics is provided in Table S1.

Outcomes

Fatigue

The analysis encompassed 89 studies, revealing an overall prevalence of fatigue at 43.3% (95% CI [36.1 − 50.9%]). Significant heterogeneity was observed (P = 0, I² = 100%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1.1). Subgroup analyses based on different follow-up periods yielded the following prevalence rates: 51% for 6 to 9 months, 24.9% for 9 to 12 months, and 60% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S1.2). When stratified by disease severity, the rates were 32.6% for severe (ICU admission), 30.7% for mild and moderate (hospital admission), and 48.7% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S1.3). Additionally, prevalence rates by study design were 38.1% for prospective, 79.3% for ambispective, 40.6% for retrospective, and 54.6% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S1.4). Egger’s test indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.0001) (Table S2).

Table 1 Summary of subgroup analysis for COVID-19 neurological sequelae by Follow-up duration

Anxiety

The analysis included 48 studies, demonstrating an overall prevalence of anxiety at 13.2% (95% CI [9.6 − 17.9%]). Significant heterogeneity was also evident (P = 0, I² = 99%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2.1). Subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods reported prevalence rates of 15.9% for 6 to 9 months, 8.7% for 9 to 12 months, and 18.5% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S2.2). Stratified by disease severity, rates were 14.2% for severe cases (ICU admission), 9.2% for mild and moderate cases (hospital admission), and 15.1% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S2.3). The prevalence by study design showed rates of 13.4% for prospective, 17.1% for ambispective, 10.1% for retrospective, and 13.7% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S2.4). Egger’s test revealed no significant publication bias (p = 0.35) (Table S2).

Cognitive impairment

This analysis included 47 studies, indicating an overall prevalence of cognitive impairment at 27.1% (95% CI [20.4 − 34.9%]). Significant heterogeneity was observed (P = 0, I² = 100%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3.1). Subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods reported prevalence rates of 27.4% for 6 to 9 months, 23.1% for 9 to 12 months, and 33.1% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S3.2). By disease severity, rates were 23.4% for severe (ICU admission), 23.7% for mild and moderate (hospital admission), and 29.1% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S3.3). The prevalence by study design was 27.4% for prospective, 45.7% for ambispective, 30.6% for retrospective, and 20.6% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S3.4). Egger’s test indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.0008) (Table S2).

Depression

The analysis comprised 55 studies, showing an overall prevalence of depression at 14.0% (95% CI [10.1 − 19.2%]). Significant heterogeneity was also present (P = 0, I² = 99%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4.1). Subgroup analyses according to follow-up periods yielded prevalence rates of 18.8% for 6 to 9 months, 6.7% for 9 to 12 months, and 19.1% for periods exceeding 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S4.2). By disease severity, rates were 12.1% for severe cases (ICU admission), 5% for mild and moderate cases (hospital admission), and 17.2% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S4.3). The prevalence by study design showed rates of 14.6% for prospective, 14.3% for ambispective, 10.2% for retrospective, and 16.3% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S4.4). Egger’s test indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.19) (Table S2).

Dizziness

The analysis involved 30 studies, indicating an overall prevalence of dizziness at 16% (95% CI [9.5 − 25.7%]). Significant heterogeneity was found (P < 0.0001, I² = 97%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5.1). Subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods yielded prevalence rates of 18.1% for 6 to 9 months, 8.7% for 9 to 12 months, and 26.1% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S5.2). By disease severity, the rates were 43.6% for severe (ICU admission), 2.4% for mild and moderate (hospital admission), and 21.9% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S5.3). The prevalence by study design was 13.9% for prospective, 40% for ambispective, 10.8% for retrospective, and 23.9% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S5.4). Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias (p = 0.11) (Table S2).

Headache

The analysis included 63 studies, indicating an overall prevalence of headaches at 20.3% (95% CI [15 − 26.9%]). Significant heterogeneity was noted (P = 0, I² = 99%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S6.1). Subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods reported prevalence rates of 24.7% for 6 to 9 months, 13.6% for 9 to 12 months, and 27% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S6.2). By disease severity, rates were 13.9% for severe (ICU admission), 6.5% for mild and moderate (hospital admission), and 28.2% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S6.3). The prevalence by study design was 18% for prospective, 36.8% for ambispective, 22.2% for retrospective, and 21.4% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S6.4). Egger’s test indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.03) (Table S2).

Memory disorders

The analysis comprised 43 studies, showing an overall prevalence of memory disorders at 27.8% (95% CI [20.1 − 37.1%]). Significant heterogeneity was present (P = 0, I² = 100%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S7.1). Subgroup analyses according to follow-up periods reported prevalence rates of 36.4% for 6 to 9 months, 17.4% for 9 to 12 months, and 14% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S7.2). By disease severity, rates were 32.7% for severe (ICU admission), 15.8% for mild and moderate (hospital admission), and 35.3% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S7.3). The prevalence by study design was 29.3% for prospective, 82% for ambispective, 25.2% for retrospective, and 22.8% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S7.4). Egger’s test indicated significant publication bias (p < 0.0001) (Table S2).

Concentration impairment

A total of 31 studies were analyzed, revealing an overall prevalence of concentration impairment at 23.8% (95% CI [17.2 − 31.9%]). Significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.0001, I² = 98%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S8.1). Subgroup analyses categorized by different follow-up periods yielded the following prevalence rates: 25.9% for 6 to 9 months, 21.7% for 9 to 12 months, and 3.6% for periods exceeding 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S8.2). Additionally, the prevalence varied according to disease severity: patients with severe conditions (ICU admission) showed a prevalence of 30.5%, while those with mild and moderate conditions (hospital admission) reported 24.3%, and outpatients (community infection) had a prevalence of 22.7% (Fig. S8.3). When stratified by study design, the prevalence was 27.4% for prospective studies, 31.7% for retrospective studies, and 12.4% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S8.4). Egger’s test indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.2) (Table S2).

Stress

The analysis included 19 studies demonstrating an overall prevalence of stress at 15.9% (95% CI [10.2 − 24%]). Notably, significant heterogeneity was found (P < 0.0001, I² = 94%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S9.1). Subgroup analyses according to different follow-up periods revealed prevalence rates of 18.4% for 6 to 9 months, 8% for 9 to 12 months, and 25% for follow-ups exceeding 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S9.2). In terms of disease severity, patients with severe conditions (ICU admission) had a prevalence of 7.2%, compared to 5.3% for mild to moderate cases (hospital admission), and 24.4% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S9.3). Furthermore, prevalence rates according to study design were 12.6% for prospective studies, 22.4% for retrospective studies, and 25% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S9.4). Egger’s test also suggested no significant publication bias (p = 0.8) (Table S2).

Sleep disorders

The analysis encompassed 59 studies, revealing an overall prevalence of sleep disorders at 24.4% (95% CI [18.1 − 32.1%]). The results indicated significant heterogeneity (P = 0, I² = 100%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S10.1). Subgroup analyses according to follow-up periods showed prevalence rates of 33.1% for 6 to 9 months, 14% for 9 to 12 months, and 39.6% for periods greater than 12 months (Table 1, Fig. S10.2). Regarding disease severity, the prevalence was 18.9% for severe conditions (ICU admission), 13.6% for mild to moderate cases (hospital admission), and 30% for outpatients (community infection) (Fig. S10.3). By study design, the prevalence rates were 19.5% for prospective studies, 22% for retrospective studies, and 36.9% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S10.4). Egger’s test indicated a significant publication bias (p < 0.0001) (Table S2).

Migraine

The analysis included five studies that reported an overall prevalence of migraine at 13% (95% CI [2.2 − 49.8%]). Significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.0001, I² = 96%) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S11.1). Subgroup analyses by study design showed prevalence rates of 55.9% for retrospective studies and 3.2% for cross-sectional studies (Fig. S11.2).

Meta-Regression

The regression analysis demonstrated that female patients exhibited significantly higher levels of stress (p = 0.0014), fatigue (p = 0.03), and headache (p = 0.001). Additionally, a higher BMI was associated with increased stress (p < 0.0001) and concentration impairment (p = 0.02). Conversely, non-smokers experienced a significant reduction in headache (p = 0.02) and cognitive impairment symptoms (p = 0.01). Long-term follow-up was also correlated with a significant decrease in memory disorders (p = 0.006) and concentration impairment (p = 0.03), as detailed in Table S3.

Quality assessment and publication Bias

The quality scores of the studies show a range primarily between 3 and 9, with the majority of scores clustering around the middle values of 5, 6, and 7. This suggests a moderate level of quality across most studies, with some achieving higher marks, reflecting a strong methodological approach, and a few scoring lower, indicating areas for potential improvement in study design or execution (Table S1). The analysis indicated that small study sizes significantly influenced the estimation of the prevalence of sleep disorders, fatigue, memory disorders, and cognitive impairment (Egger’s test: p < 0.001), as well as headache (Egger’s test: p = 0.03). However, no significant publication bias was observed for other symptoms, including dizziness, stress, anxiety, concentration impairment, and depression (Egger’s test: p > 0.05) (Table S2 and funnel plot in Figs. S12.1 to 12.10).

Discussion

This systematic review investigated a range of symptoms associated with long COVID, providing a detailed overview of its extensive impact on affected individuals. The findings revealed high prevalence rates for several symptoms, underscoring the significant burden of this condition. Fatigue emerged as the most frequently reported symptom among long COVID patients. Cognitive challenges, including memory difficulties (commonly referred to as “brain fog”) and cognitive impairments, were also highly prevalent. Sleep disturbances were commonly observed, alongside attention impairments and frequent reports of headaches. Mental health impacts were significant, with anxiety, depression, and stress frequently noted among patients. Other symptoms, such as dizziness and migraines, further added to the burden experienced by individuals with long COVID.

The neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms observed in long COVID appear to be multifactorial, arising from interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms [148,149,150,151,152,153]. Neuroinflammation, a hallmark of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is driven by the activation of microglia and astrocytes, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [154, 155]. These cytokines impair synaptic plasticity and neuronal functioning, which are critical to cognitive processes, and have been associated with mood disorders, cognitive decline, and sleep disturbances. Additionally, autonomic nervous system dysregulation has been implicated in exacerbating mood and cognitive impairments [156, 157]. Autonomic dysfunction may contribute to symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue, and attention difficulties, possibly through alterations in heart rate variability and blood flow to the brain. Dysregulation of neurotransmitters, including serotonin and dopamine, may further compound neuropsychiatric symptoms, manifesting as anxiety, depression, and stress. Another critical factor is endothelial dysfunction, which results in microvascular damage [158, 159]. This damage, combined with systemic inflammation, can lead to impaired cerebral perfusion, further intensifying neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms. Evidence also points to hypertension and other vascular comorbidities as potential amplifiers of these effects, creating a vicious cycle of symptom exacerbation.

Our study found that 24.4% of 1,544,695 patients experienced sleep difficulties, a prevalence significantly higher than the 13.5% reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 731,679 patients [160]. Sleep disturbances in long COVID can result from multiple factors, including neuroinflammation disrupting hypothalamic regulation of sleep-wake cycles and secondary effects such as persistent respiratory symptoms (e.g., coughing and shortness of breath). Additionally, medications such as corticosteroids can exacerbate insomnia. These disruptions significantly impair daily functioning, reducing productivity and increasing the risk of accidents due to fatigue [160,161,162,163,164,165,166]. Headaches were reported by 20.3% of 127,133 patients in our study, contrasting with the 11.5% observed by Zeng et al. (2023) among 44,066 patients [160]. The heightened prevalence may stem from SARS-CoV-2-induced dysregulation of ACE2 activity, leading to altered angiotensin II levels, elevated blood pressure, and increased intracranial pressure. Neuroinflammation and autonomic nervous system dysfunction also likely contribute to headache severity and frequency [160, 167,168,169,170].

Our study showed that 16% of 9,370 patients experienced dizziness, higher than the 9.7% among 7,427 patients in Zeng et al. (2023) [160]. Vestibular dysfunction caused by viral invasion of the inner ear and neural pathways may underlie this symptom. Additionally, side effects of medications or prolonged immobilization during acute illness could exacerbate dizziness [160, 171,172,173]. We reported that 14% of 1,532,073 patients experienced depression, slightly lower than the 18.3% reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 484,106 patients [160]. Contributing factors to depression in long COVID include neuroinflammation, cytokine production, dysregulated neurotransmitter systems, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Psychosocial stressors, such as chronic fatigue, isolation, and reduced quality of life, further exacerbate depressive symptoms. Sleep disturbances and cognitive impairments frequently co-occur, compounding the risk of clinical depression [160, 174,175,176,177]. Similarly, anxiety was reported in 13.2% of 1,529,852 patients, lower than the 16.2% reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 721,541 patients. Anxiety in long-term COVID-19 patients is driven by similar pathophysiological mechanisms as depression, including neuroinflammation and autonomic dysfunction. Chronic stress and uncertainty about health recovery further contribute to the prevalence of anxiety [160, 174, 178, 179].

Our findings indicated that 27.8% of 1,299,214 patients experienced memory problems, a prevalence significantly higher than the 17.5% reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 7,322 patients. This elevated prevalence may stem from multiple interconnected mechanisms, including neuroinflammation, disrupted neurotransmitter activity, and irregular sleep patterns, all known to impair hippocampal function. The hippocampus is vital for memory consolidation, learning, and neurogenesis, specifically through the production of neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus. However, this brain region is particularly vulnerable to neurodegenerative processes and psychiatric disorders, which may be amplified by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Evidence suggests that the hippocampus is a primary target of the virus’s effects, contributing to post-infection memory loss through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, cytokine-driven inflammation, and vascular damage [160, 165, 180].

Attention impairment was observed in 23.8% of 6,911 patients in our analysis, markedly higher than the 12.6% reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 6,977 patients. Like memory impairment, attention deficits in long COVID are likely driven by neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter dysregulation, and sleep disturbances. These mechanisms disrupt cortical and subcortical networks essential for sustained and selective attention. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular injury, hallmarks of long COVID, may reduce oxygenation to key brain regions, exacerbating cognitive impairments. Psychological stress, anxiety, and fatigue may also contribute to these deficits by reducing neural efficiency and promoting cognitive overload [149, 160, 173, 180,181,182].

Our study further found that 27.1% of 1,417,411 patients exhibited cognitive impairment, compared to the 19.7% prevalence reported by Zeng et al. (2023) among 2,256 patients. The higher prevalence in our analysis underscores the extensive impact of SARS-CoV-2 on brain function. Cognitive impairment in long COVID patients is linked to systemic inflammation, altered neurotransmitter dynamics, and endothelial damage, leading to reduced cerebral perfusion. Hypoxia, ischemia, immune dysregulation, and sleep disturbances may further amplify these effects, alongside psychological factors such as chronic stress and deconditioning during prolonged illness. Emerging evidence suggests that persistent cognitive impairments reflect the cumulative impact of these multifaceted mechanisms on neural networks responsible for executive function, processing speed, and working memory [160, 183,184,185].

Neuropsychiatric symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairments compound the challenges faced by severely affecting daily functioning and emotional wellbeing. Depression and anxiety, in particular, amplify the negative effects of long COVID by interfering with social interactions and reducing overall mental health, which in turn can adversely affect work performance and relationships [170]. The cumulative burden of these symptoms significantly diminishes the quality of life, restricting individuals’ ability to engage in professional and personal activities.

Current evidence indicates that blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction is linked to abnormal brain iron deposition and cognitive decline across various neurological conditions, potentially including COVID-19 complications. Higher APOE ɛ4 dosage has been associated with reduced BBB clearance and increased iron and β-amyloid accumulation [186]. In CADASIL, greater BBB permeability correlates with more pronounced iron leakage and cognitive impairment [187]. Similar relationships between brain iron dynamics and BBB function have been observed in pediatric populations [188] and in ischemic stroke, where changes in magnetic susceptibility correlate with neurological outcomes [189]. Together, these findings suggest a convergent pathway that may contribute to neurodegeneration and recovery processes.

Despite increasing recognition of these sequelae, effective management strategies remain limited, and further research is needed to develop targeted interventions. Pharmacological management is an active area of investigation, with ongoing trials evaluating the efficacy of antidepressants, anti-inflammatory agents, and neuromodulatory drugs for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms in long COVID [190]. However, these trials are still in their early phases, and no standardized treatment protocol has been established.

Given this uncertainty, a multidisciplinary approach integrating cognitive rehabilitation, psychological support, and pharmacological interventions is emerging as a promising strategy. A comprehensive neuropsychological intervention program incorporating psychoeducation, restorative techniques, and compensatory strategies has demonstrated potential in addressing cognitive deficits and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms [191]. Similarly, neuropsychiatric associations emphasize the need for a structured clinical framework for assessing and managing post-COVID neuropsychiatric sequelae, with a focus on symptom-based treatment approaches [165]. A recent systematic review by Zeraatkar et al. (2024) further supports the role of multidisciplinary interventions in managing long COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms [192]. The analysis of 24 trials (n = 3,695) found that online cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) effectively reduced fatigue and improved concentration, while a supervised rehabilitation program integrating physical and mental health interventions enhanced overall health, reduced depression, and improved quality of life [192]. Intermittent aerobic exercise (3–5 times per week for 4–6 weeks) also showed greater benefits for physical function than continuous exercise. However, no compelling evidence was found for pharmacological treatments, reinforcing the importance of psychological and rehabilitative approaches in long COVID management.

In addition to cognitive and psychological interventions, neuromodulatory approaches are gaining attention. A pilot randomized controlled trial assessing transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation demonstrated its feasibility as a noninvasive home-based intervention, with preliminary findings suggesting potential improvements in mental fatigue and related symptoms [193]. This aligns with increasing interest in targeting inflammatory pathways in long COVID, as dysregulation of interleukin-6 (IL-6) has been proposed as a key mediator of prolonged neuropsychiatric symptoms [194]. Given the heterogeneity of neuropsychiatric manifestations in long COVID, personalized treatment approaches tailored to individual patient profiles, symptom severity, and underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are essential. Large-scale clinical trials and longitudinal studies are needed to refine therapeutic strategies and establish evidence-based guidelines for managing these persistent and often debilitating symptoms.

Addressing long COVID requires a proactive, multidisciplinary approach, particularly in resource-limited settings where healthcare capacity may be constrained. Comprehensive care strategies should prioritize the management of sleep disturbances and neuropsychiatric symptoms through cognitive-behavioral therapy, pharmacological treatments, and rehabilitation programs aimed at alleviating symptom severity and restoring functionality. These strategies are essential for mitigating the long-term societal and economic impacts of long COVID while improving patient outcomes [195,196,197,198]. Efforts should emphasize accessibility, equity, and innovation in healthcare delivery, focusing on scalable solutions to meet the complex needs of long COVID patients globally. Developing evidence-based guidelines and fostering cross-disciplinary collaboration will be crucial in shaping effective public health responses to the long-term consequences of COVID-19.

Our meta-regression analysis found that female gender is significantly associated with certain long COVID symptoms, likely due to biological and psychosocial factors. Biologically, women’s stronger immune responses may increase inflammation, leading to symptoms like fatigue and headaches [199, 200]. Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone might also influence immune responses and pain perception. Psychosocial factors, including caregiving roles and societal expectations, may enhance symptom reporting, contributing to a higher symptom burden in women [201]. Additionally, we found significant associations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and factors like BMI, smoking status, and the duration of follow-up, while age and ethnicity were not significantly correlated. Higher BMI was linked to persistent fatigue, possibly due to inflammation from excess adipose tissue releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can prolong neuroinflammatory responses and reduce energy levels [202,203,204,205,206,207]. Beyond biological mechanisms, psychological stress and social stigma related to obesity might also worsen neuropsychiatric symptoms, affecting long COVID recovery. These results highlight the complex interactions of demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors in post-COVID-19 neuropsychiatric sequelae. The variability in outcomes may be influenced by population characteristics, geographic location, cultural factors, and study methodologies, such as inconsistencies in follow-up periods and potential publication bias. The significant variability across studies limits defining a precise critical period for intervention. Symptoms tend to peak within the first few months post-infection, but their trajectories vary, necessitating early intervention and long-term follow-up to manage recurrent or prolonged effects. The heterogeneity in symptom prevalence across patient groups highlights the need for standardized protocols and robust methodologies in future research to ensure comparability and reliability, as well as individualized approaches in managing long COVID.

Strengths and limitations

This meta-analysis has several notable strengths. First, its comprehensive scope, incorporating 125 studies with over 4 million patients, enhances the generalizability of findings and provides a robust dataset for understanding the long-term neuropsychiatric effects of COVID-19. Second, the use of strict inclusion criteria and rigorous methodological approaches bolsters the credibility of the results. Additionally, the focus on long-term follow-up, with symptoms assessed at least six months post-infection, offers critical insights into the enduring impacts of COVID-19 on mental health. By highlighting the multifaceted nature of symptoms—such as the interplay between cognitive impairments, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances—the analysis presents a comprehensive view of post-COVID neuropsychiatric health, aiding clinicians in tailoring interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Despite these strengths, this meta-analysis has notable limitations that warrant careful consideration. One significant limitation is the heterogeneity observed across the included studies, which varied in design, populations, and methodologies. This variability complicates direct comparisons and limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, differences in follow-up periods across studies may have affected symptom prevalence rates. Standardizing follow-up periods in future research would enhance clarity and comparability. Publication bias also poses a challenge, as studies with positive findings are more likely to be published, potentially skewing the results. Additionally, the quality of data extracted from the included studies varied, with inconsistencies in how symptoms were defined, measured, and reported. Reliance on self-reported data in some studies introduces variability and may limit accuracy due to measurement bias that can affect prevalence estimates; therefore, future studies should strive to incorporate objective assessments where possible. While the study accounted for several demographic and health-related factors, residual confounding remains a possibility, as unmeasured variables such as socioeconomic status, comorbid conditions, and lifestyle factors could influence symptom prevalence. Lastly, the predominance of cross-sectional data limits the ability to infer causal relationships between COVID-19 and the reported symptoms. Longitudinal studies are necessary to establish temporal relationships and better understand symptom progression in post-COVID patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis highlights the significant prevalence of long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with COVID-19, including fatigue, depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, and headaches. These persistent issues underscore the need for healthcare systems to prioritize mental health and cognitive care for post-COVID-19 patients. Comprehensive, multidisciplinary strategies that address both physical and mental health are essential to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Such efforts will support the development of targeted treatments, mitigating the pandemic’s enduring impact on mental health and enhancing overall wellbeing.