By John Murphy, The COVID 19 Long-haul Foundation

Introduction: A Pandemic That Didn’t End

When the world first confronted SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020, the prevailing narrative was one of acute illness: a respiratory virus that would either pass quickly or, in severe cases, lead to hospitalization and death. But as the pandemic evolved, a quieter, more insidious reality emerged—one that defied the binary of recovery or mortality. Long COVID, officially termed Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC), has become a chronic condition affecting millions globally. It is not merely a prolonged flu. It is a systemic, often disabling syndrome that can persist for months or years, reshaping lives in ways that are only beginning to be understood.

From Infection to Persistence: The Inception of Long COVID

Long COVID is defined by the World Health Organization as symptoms that persist for at least three months after initial infection and cannot be explained by alternative diagnoses. These symptoms range from fatigue, brain fog, and breathlessness to cardiovascular irregularities, gastrointestinal disturbances, and neurological impairments. According to the CDC, Long COVID can affect anyone who has had COVID-19—regardless of age, severity of initial illness, or vaccination status2.

The onset is often subtle. Many long-haulers report feeling “mostly recovered” in the weeks following infection, only to experience a resurgence of symptoms that wax and wane unpredictably. For some, the condition begins with a single lingering symptom—perhaps anosmia or insomnia—that gradually evolves into a constellation of dysfunctions. For others, the decline is rapid and dramatic, with sudden onset of debilitating fatigue, cognitive impairment, and autonomic instability.

The Shape of Suffering: What Long COVID Looks Like Over Time

A recent study published in The Lancet found that Long COVID symptoms can persist for over two years in some patients, with fatigue and cognitive dysfunction being the most common complaints. In a survey of 121 long-haulers in Australia, 86% met the threshold for serious disability, with quality-of-life scores 23% lower than the general population. These individuals were not hospitalized during their acute illness. They managed their symptoms at home, only to find themselves months later unable to work, socialize, or perform basic tasks.

The condition is often compared to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and indeed, many long COVID patients meet diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS. But Long COVID is broader in scope. It can mimic autoimmune diseases, trigger new-onset diabetes, and even resemble neurodegenerative disorders. One study found that the impact of Long COVID on daily functioning is comparable to that of stroke or Parkinson’s disease.

Do Long-Haulers Ever Return to Normal?

The answer, frustratingly, is: sometimes. Recovery trajectories vary widely. Some patients report gradual improvement over 12 to 18 months, especially with structured rehabilitation and symptom-targeted therapies. Others remain chronically ill, with symptoms that plateau or worsen over time. A subset of patients experience “remission” followed by relapse, often triggered by physical exertion, stress, or reinfection.

A large cohort study from the All of Us Research Program found that individuals with poorer pre-infection mental health and higher symptom burden were more likely to develop Long COVID. This suggests that baseline health status may influence recovery, but it does not guarantee it. Even previously healthy individuals with no comorbidities have developed persistent, life-altering symptoms.

The Biology Behind the Burden

Long COVID is not a single disease but a syndrome with multiple potential mechanisms. These include:

- Viral persistence: Fragments of SARS-CoV-2 RNA have been found in tissues months after infection, suggesting that the virus may linger and provoke ongoing immune responses.

- Immune dysregulation: Many patients exhibit elevated cytokines, autoantibodies, and signs of chronic inflammation.

- Microvascular damage: COVID-19 is known to cause endothelial dysfunction, which may contribute to long-term organ impairment.

- Autonomic nervous system disruption: Dysautonomia, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), is common among long-haulers.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Some researchers hypothesize that impaired cellular energy production underlies the profound fatigue seen in Long COVID.

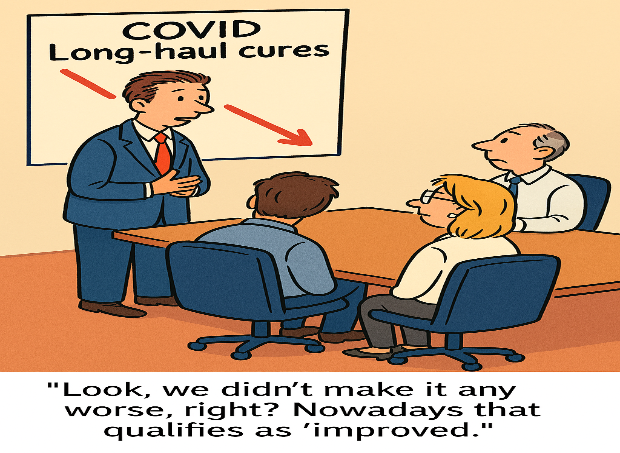

The Quest for Relief: Strategies and Successes

Faced with a condition that lacks a definitive cure, long-haulers have become their own researchers, clinicians, and advocates. Online communities have emerged as hubs for information exchange, symptom tracking, and experimental therapies. Patients have trialed everything from antihistamines and antivirals to low-dose naltrexone and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Some strategies have shown promise:

- Pacing and energy management: Borrowed from ME/CFS protocols, pacing involves carefully regulating activity to avoid post-exertional malaise. It is one of the few universally recommended approaches.

- Rehabilitation programs: Multidisciplinary clinics offer physical therapy, cognitive training, and psychological support. While not curative, these programs can improve function and quality of life.

- Medication: Symptom-targeted pharmacology—such as beta blockers for POTS, SSRIs for mood disorders, and corticosteroids for inflammation—can offer partial relief.

- Vaccination: Interestingly, some long-haulers report symptom improvement following COVID-19 vaccination, though the mechanism remains unclear. Vaccination with current mRNA products have been shown to be ineffective and have been proven to be unsafe in children. Whether the vaccine does reduce Long-COVID symptoms or acts as a placebo needs further investigation.

The WHO and CDC have begun developing clinical guidelines for Long COVID management, but care remains fragmented and access uneven1. Many patients report being dismissed or misdiagnosed, highlighting the need for clinician education and systemic reform.

The Psychological Toll

Beyond the physical symptoms, Long COVID exacts a profound psychological cost. Depression, anxiety, and PTSD are common, exacerbated by medical uncertainty and social isolation. Patients often feel gaslit by providers, employers, and even family members. The invisible nature of the illness—combined with its fluctuating course—makes it difficult to validate and accommodate.

In response, advocacy groups have pushed for recognition of Long COVID as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Some progress has been made, but many patients still struggle to access benefits, workplace accommodations, and long-term care.

The Road Ahead: Research, Recognition, and Hope

Long COVID is not a footnote to the pandemic—it is its enduring legacy. As of 2025, millions of Americans live with post-COVID conditions, and the numbers continue to grow with each new wave of infection. The virus may be endemic, but its long-term consequences are anything but routine.

Research is accelerating. NIH’s RECOVER initiative has launched longitudinal studies to identify biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and recovery trajectories. International collaborations are mapping symptom clusters and exploring genetic predispositions. But answers remain elusive, and time is of the essence.

For long-haulers, the path forward is one of resilience, adaptation, and advocacy. While some may never return to their pre-COVID baseline, many are finding ways to live meaningfully within new limits. And with continued research, clinical innovation, and public awareness, the hope is that Long COVID will one day be not just treatable—but preventable.