John Murphy, CEO COVID-19 Long-haul Foundation

Abstract

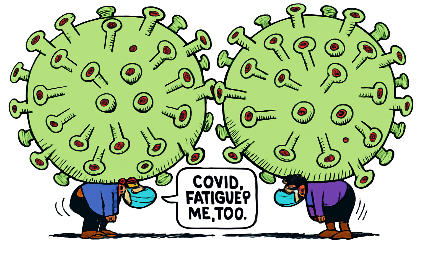

Fatigue is the most prevalent and disabling symptom among survivors of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection, persisting in a substantial proportion of patients months to years after acute illness. Unlike ordinary tiredness, COVID‑related fatigue is characterized by profound exhaustion, post‑exertional malaise, and cognitive impairment, often resembling myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). The etiology is multifactorial, involving viral persistence, immune dysregulation, microvascular injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, and autonomic imbalance. Genomic susceptibility factors, including HLA variants and ACE2 polymorphisms, appear to modulate risk. Pathophysiological studies reveal endothelial dysfunction, microclots, neuroinflammation, and altered connectivity in brain nuclei such as the thalamus and basal ganglia. Sleep disturbance is common, with polysomnography demonstrating circadian rhythm disruption and non‑restorative sleep. Current treatments remain symptomatic, ranging from pacing and rehabilitation to experimental immunomodulators and antifibrotics. Prognosis varies, with some patients recovering within a year while others develop chronic disability. This article synthesizes current evidence across molecular, physiological, and clinical domains to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding COVID fatigue and guiding future therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Fatigue is the most common and disabling symptom reported by survivors of COVID‑19, affecting between 45% and 65% of patients three months after acute infection. It is not merely a subjective complaint but a multidimensional syndrome encompassing physical exhaustion, cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”), sleep disturbance, and autonomic instability. The persistence of fatigue has profound implications for public health, workforce participation, and healthcare systems worldwide.

Historically, post‑viral fatigue syndromes have been documented following outbreaks of Epstein‑Barr virus, influenza, and other coronaviruses (e.g., SARS‑CoV‑1, MERS). However, the scale of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection has created an unprecedented burden. Millions of individuals globally report ongoing fatigue, with many unable to return to baseline functioning. The overlap with ME/CFS has prompted renewed interest in mechanisms of post‑infectious fatigue, while the unique features of COVID‑related fatigue suggest novel pathophysiological pathways.

This manuscript aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge regarding COVID fatigue, spanning etiology, genomics, physiology, pathology, neurobiology, sleep disturbance, treatment, and prognosis. By integrating evidence from molecular biology, neuroimaging, and clinical studies, we seek to establish a framework for understanding and addressing this disabling condition.

Etiology of COVID Fatigue

1. Viral Persistence

Evidence suggests that fragments of SARS‑CoV‑2 RNA and proteins may persist in tissues long after acute infection. Autopsy studies have identified viral remnants in lung, gut, and brain tissue months after recovery. Persistent antigens may provoke chronic immune activation, leading to sustained fatigue. This mechanism parallels findings in other post‑viral syndromes, where incomplete viral clearance drives ongoing inflammation.

2. Immune Dysregulation

COVID fatigue is strongly associated with immune abnormalities. Elevated cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α, interferon‑γ) have been documented in long‑COVID cohorts. These cytokines can cross the blood‑brain barrier, altering neurotransmission and contributing to “sickness behavior” — a conserved biological response characterized by fatigue, anhedonia, and cognitive slowing. Dysregulated T‑cell responses, including exhaustion phenotypes, further impair immune resolution.

3. Microvascular Injury

Microclots and endothelial dysfunction are increasingly recognized as contributors to long‑COVID fatigue. Studies using fluorescence microscopy have identified amyloid microclots resistant to fibrinolysis in patient plasma. These microclots impair oxygen delivery, leading to tissue hypoxia and mitochondrial stress. Endothelial injury also disrupts nitric oxide signaling, impairing vascular tone and contributing to exercise intolerance.

4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria are central to energy metabolism, and dysfunction has been implicated in both ME/CFS and COVID fatigue. Muscle biopsies reveal reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity, while metabolomic studies show altered lactate and pyruvate profiles. Mitochondrial dysfunction may result from direct viral effects, cytokine‑mediated damage, or hypoxia induced by microvascular injury. The net effect is impaired ATP production, manifesting as profound fatigue.

5. Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other dysautonomias are common in long‑COVID. Patients experience tachycardia, dizziness, and fatigue upon standing, reflecting impaired autonomic regulation. Mechanisms may include autoimmune attack on adrenergic receptors, viral damage to autonomic ganglia, or persistent inflammation. Autonomic imbalance exacerbates fatigue by disrupting cardiovascular and metabolic homeostasis.

6. Autoimmune Hypotheses

Autoantibodies targeting G‑protein coupled receptors, endothelial antigens, and neural proteins have been identified in long‑COVID patients. These autoantibodies may interfere with neurotransmission, vascular function, and immune regulation. The autoimmune hypothesis aligns with the observation that fatigue often coexists with other autoimmune phenomena, such as thyroiditis or lupus‑like syndromes.

Summary of Etiology

COVID fatigue arises from a complex interplay of viral persistence, immune dysregulation, microvascular injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, autonomic imbalance, and autoimmunity. These mechanisms converge to disrupt energy metabolism, oxygen delivery, and neural signaling, producing the multidimensional fatigue syndrome observed in survivors.

Genomics of COVID Fatigue

1. Host Genetic Susceptibility

Emerging evidence suggests that host genetics play a critical role in determining susceptibility to long‑COVID fatigue. Genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several loci associated with persistent symptoms. Variants in the HLA region appear particularly relevant, reflecting the importance of antigen presentation in immune resolution. Certain HLA alleles may predispose individuals to aberrant immune responses, prolonging inflammation and contributing to fatigue.

Polymorphisms in ACE2, the receptor for SARS‑CoV‑2, have also been implicated. Variants that alter receptor binding affinity may influence viral persistence in tissues, particularly in the lungs and brain. Similarly, polymorphisms in TMPRSS2, a protease facilitating viral entry, may modulate infection dynamics and subsequent risk of chronic symptoms.

2. Immune Regulation Genes

Genes regulating cytokine production and immune signaling are central to the pathogenesis of COVID fatigue. Variants in IL‑6, TNF‑α, and interferon pathways have been associated with heightened inflammatory responses. Individuals with pro‑inflammatory genotypes may experience exaggerated cytokine storms during acute infection, followed by persistent immune activation that manifests as fatigue.

Epigenetic modifications also play a role. DNA methylation changes in immune cells have been observed in long‑COVID patients, suggesting that viral infection induces lasting alterations in gene expression. These epigenetic shifts may perpetuate immune dysregulation even after viral clearance.

3. Mitochondrial Genomics

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variants influence energy metabolism and may predispose individuals to fatigue. Haplogroups associated with reduced oxidative phosphorylation efficiency have been linked to higher risk of post‑viral fatigue syndromes. In COVID fatigue, mitochondrial dysfunction is a consistent finding, and mtDNA variants likely modulate susceptibility.

Studies have identified increased mtDNA damage in long‑COVID patients, reflecting oxidative stress and impaired repair mechanisms. This damage may impair ATP production, contributing to the profound exhaustion characteristic of the syndrome.

4. Viral Genomics

The genomic characteristics of SARS‑CoV‑2 itself may influence the risk of long‑COVID fatigue. Variants with mutations in the spike protein may alter tissue tropism, increasing the likelihood of viral persistence in the central nervous system or other organs. Mutations in non‑structural proteins involved in immune evasion may prolong viral survival, sustaining immune activation and fatigue.

The Omicron variant, for example, has been associated with lower rates of hospitalization but persistent reports of long‑COVID symptoms, including fatigue. This suggests that viral genomic differences may modulate the balance between acute severity and chronic sequelae.

5. Neurogenomics

Fatigue is closely linked to neural signaling, and genetic variants affecting neurotransmitter systems may contribute. Polymorphisms in dopamine and serotonin transporters have been associated with fatigue and cognitive dysfunction in other conditions. In COVID fatigue, similar variants may exacerbate neurochemical imbalances induced by inflammation and viral persistence.

Neurogenomic studies also highlight the role of BDNF (brain‑derived neurotrophic factor), a gene critical for synaptic plasticity. Reduced BDNF expression has been observed in long‑COVID patients, potentially impairing neural recovery and contributing to fatigue.

6. Integrative Genomic Models

The complexity of COVID fatigue requires integrative models that combine host and viral genomics with epigenetic and transcriptomic data. Systems biology approaches have begun to map networks of gene interactions underlying fatigue. These models highlight convergence on pathways regulating immune activation, mitochondrial function, and neural signaling.

Machine learning applied to genomic datasets may eventually allow prediction of individual risk for long‑COVID fatigue. Such predictive models could guide personalized interventions, identifying patients most likely to benefit from specific therapies.

Summary of Genomics

Genomic factors play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of COVID fatigue. Host genetic susceptibility, immune regulation variants, mitochondrial haplogroups, viral mutations, and neurogenomic polymorphisms converge to shape individual risk. Epigenetic modifications further perpetuate dysregulation, sustaining fatigue long after acute infection. Understanding these genomic influences is essential for developing targeted therapies and predictive models.

Physiology of COVID Fatigue

1. Energy Metabolism Disruption

One of the most consistent physiological findings in COVID fatigue is impaired energy metabolism. Patients frequently report exhaustion disproportionate to exertion, a hallmark of mitochondrial dysfunction. Muscle biopsies and metabolomic analyses reveal reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity, elevated lactate accumulation, and altered pyruvate metabolism. These changes suggest a shift from aerobic to anaerobic energy production, leading to inefficient ATP generation and rapid fatigue.

Functional MRI studies demonstrate reduced cerebral oxygen utilization, consistent with impaired metabolic coupling between neurons and glial cells. This disruption may underlie cognitive symptoms such as brain fog. The persistence of metabolic abnormalities months after infection indicates a chronic physiological state rather than transient deconditioning.

2. Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance

Autonomic dysfunction is a prominent feature of long‑COVID fatigue. Patients often present with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), characterized by excessive heart rate increase upon standing, dizziness, and fatigue. Tilt‑table testing confirms autonomic instability, while heart rate variability analyses reveal reduced parasympathetic tone.

Mechanistically, autonomic imbalance may result from autoimmune attack on adrenergic and muscarinic receptors, viral damage to autonomic ganglia, or persistent inflammation. Dysautonomia exacerbates fatigue by impairing cardiovascular regulation, leading to inadequate cerebral perfusion during exertion. This explains why patients often experience post‑exertional malaise after minimal activity.

3. Cardiopulmonary Limitations

Cardiopulmonary physiology is frequently altered in long‑COVID fatigue. Pulmonary function tests reveal reduced diffusion capacity, reflecting microvascular injury and alveolar damage. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) demonstrates reduced peak oxygen uptake (VO₂ max) and early anaerobic threshold, consistent with impaired oxygen delivery and utilization.

Endothelial dysfunction contributes to these limitations. Damage to vascular endothelium impairs nitric oxide signaling, reducing vasodilation and oxygen transport. Microclots further obstruct capillary flow, leading to tissue hypoxia. These cardiopulmonary abnormalities manifest clinically as exertional dyspnea and profound fatigue.

4. Neuroendocrine Dysregulation

The hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal (HPA) axis is frequently disrupted in long‑COVID fatigue. Cortisol levels may be blunted, reflecting adrenal insufficiency, or elevated, reflecting chronic stress. Both extremes impair energy regulation and contribute to fatigue. Dysregulation of thyroid hormones has also been reported, with some patients developing autoimmune thyroiditis post‑COVID.

Neuroendocrine imbalance extends to sex hormones. Altered estrogen and testosterone levels may influence fatigue severity, particularly in women, who are disproportionately affected by long‑COVID. These hormonal changes interact with immune and metabolic pathways, creating a complex physiological landscape.

5. Sleep Physiology

Sleep disturbance is both a symptom and a physiological contributor to fatigue. Polysomnography reveals fragmented sleep, reduced slow‑wave sleep, and circadian rhythm disruption. These abnormalities impair restorative processes, exacerbating fatigue and cognitive dysfunction. Sleep physiology is further disrupted by autonomic imbalance, with patients experiencing nocturnal tachycardia and poor sleep quality.

6. Integrative Physiological Model

COVID fatigue reflects a convergence of physiological disruptions: impaired energy metabolism, autonomic imbalance, cardiopulmonary limitations, neuroendocrine dysregulation, and sleep disturbance. These systems interact dynamically, creating a self‑reinforcing cycle of fatigue. For example, microvascular injury impairs oxygen delivery, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, which exacerbates autonomic instability and sleep disruption. The result is a multidimensional syndrome resistant to simple interventions.

Summary of Physiology

The physiology of COVID fatigue is characterized by systemic disruption across energy metabolism, autonomic regulation, cardiopulmonary function, neuroendocrine signaling, and sleep architecture. These abnormalities converge to produce profound, persistent fatigue that impairs daily functioning. Understanding these physiological mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapies and guiding rehabilitation strategies.

1. Histopathological Findings in Muscle Tissue

Muscle biopsies from long‑COVID patients frequently reveal abnormalities consistent with chronic fatigue syndromes. Histology demonstrates fiber atrophy, mitochondrial swelling, and disrupted sarcomere architecture. Electron microscopy highlights reduced cristae density within mitochondria, correlating with impaired oxidative phosphorylation. Inflammatory infiltrates, predominantly T lymphocytes and macrophages, are often present, suggesting ongoing immune activation. These findings support the hypothesis that muscle pathology contributes directly to fatigue by impairing contractile efficiency and energy metabolism.

2. Brain Pathology

Neuropathological studies reveal microglial activation, astrocytic hypertrophy, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the brains of long‑COVID patients. MRI and PET imaging corroborate these findings, showing evidence of neuroinflammation and altered glucose metabolism in regions such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem nuclei. Autopsy studies have identified viral RNA and proteins in neural tissue months after infection, suggesting persistent antigenic stimulation. These pathological changes likely underlie cognitive dysfunction and central fatigue.

3. Lung Pathology

Persistent respiratory symptoms in long‑COVID fatigue are linked to structural lung changes. Histology demonstrates fibrosis, alveolar damage, and endothelial injury. Microvascular pathology is particularly striking, with widespread capillary rarefaction and microclot deposition. These changes impair gas exchange, contributing to exertional dyspnea and systemic fatigue. The overlap with post‑ARDS fibrosis highlights the chronic nature of pulmonary pathology in COVID survivors.

4. Microclots and Endothelial Dysfunction

One of the most distinctive pathological features of long‑COVID is the presence of amyloid microclots in circulation. These clots are resistant to fibrinolysis and obstruct capillary flow, leading to tissue hypoxia. Endothelial cells show evidence of apoptosis, disrupted tight junctions, and reduced nitric oxide production. Together, these changes impair vascular homeostasis, perpetuating fatigue by limiting oxygen delivery to tissues.

5. Neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation is a central pathological mechanism in COVID fatigue. Activated microglia release pro‑inflammatory cytokines, disrupting synaptic transmission and impairing neuroplasticity. Astrocytic dysfunction further compromises metabolic support for neurons. These changes are particularly pronounced in brain nuclei regulating arousal and energy, such as the thalamus and hypothalamus. The result is impaired central regulation of fatigue, manifesting clinically as brain fog and cognitive slowing.

6. Immune Pathology

Persistent immune activation is evident in lymphoid tissues, with germinal center disruption and aberrant B‑cell maturation. Autoantibody production against neural and vascular antigens has been documented, supporting the autoimmune hypothesis. Chronic immune pathology sustains systemic inflammation, contributing to fatigue and multi‑organ dysfunction.

7. Comparative Pathology

The pathological features of COVID fatigue overlap with those observed in ME/CFS and other post‑viral syndromes, including mitochondrial abnormalities, neuroinflammation, and microvascular injury. However, the prominence of amyloid microclots and endothelial dysfunction appears unique to COVID, suggesting distinct mechanisms. Comparative pathology underscores both shared and novel pathways in post‑infectious fatigue.

Summary of Pathology

Pathological studies reveal a multifaceted landscape in COVID fatigue: muscle fiber atrophy and mitochondrial disruption, neuroinflammation and viral persistence in the brain, pulmonary fibrosis and endothelial injury, and systemic microclots impairing oxygen delivery. These findings converge to produce a syndrome of profound fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and exertional intolerance. Pathology provides critical insight into mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

Changes in Brain Nuclei in COVID Fatigue

1. Thalamus

The thalamus serves as a central relay station for sensory and motor signals, and its integrity is critical for maintaining arousal and cognitive function. Neuroimaging studies in long‑COVID patients reveal reduced thalamic volume, altered connectivity, and hypometabolism. PET scans demonstrate diminished glucose uptake, suggesting impaired neuronal activity. These changes correlate with clinical symptoms of fatigue, slowed processing speed, and attentional deficits. Pathological studies confirm microglial activation and perivascular inflammation within thalamic nuclei, implicating immune‑mediated injury.

2. Basal Ganglia

The basal ganglia, particularly the caudate and putamen, are implicated in motor control and motivational states. MRI studies show signal abnormalities and reduced functional connectivity in these regions among long‑COVID patients. Dysfunction of dopaminergic pathways within the basal ganglia may contribute to both physical fatigue and anhedonia. Altered dopamine transporter availability has been documented, suggesting impaired neurotransmission. These findings parallel those observed in Parkinson’s disease and ME/CFS, highlighting shared neurobiological mechanisms.

3. Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus regulates neuroendocrine and autonomic functions, both of which are disrupted in COVID fatigue. MRI studies reveal structural changes and altered connectivity in hypothalamic nuclei. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal (HPA) axis is evident, with abnormal cortisol rhythms and impaired stress responses. Hypothalamic injury may also contribute to sleep disturbance, given its role in circadian rhythm regulation. Persistent inflammation and viral antigen presence have been documented in hypothalamic tissue, supporting a direct pathological role.

4. Brainstem Nuclei

The brainstem contains nuclei critical for autonomic regulation, including the locus coeruleus and dorsal vagal complex. Neuroimaging demonstrates signal changes and reduced connectivity in these regions among long‑COVID patients. Dysfunction of the locus coeruleus, a major source of noradrenaline, may impair arousal and contribute to fatigue. Damage to vagal nuclei disrupts autonomic balance, exacerbating dysautonomia and post‑exertional malaise. These findings underscore the role of brainstem pathology in the physiological manifestations of fatigue.

5. Default Mode Network and Connectivity

Functional MRI studies reveal widespread disruption of the default mode network (DMN), which integrates activity across thalamic, basal ganglia, and cortical regions. Reduced connectivity within the DMN correlates with cognitive dysfunction and fatigue severity. These changes suggest that COVID fatigue is not confined to isolated nuclei but reflects network‑level disruption. Altered connectivity may result from neuroinflammation, microvascular injury, and neurotransmitter imbalance.

6. Neurochemical Shifts

Neurochemical studies highlight alterations in dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate signaling within brain nuclei. Reduced dopamine transporter availability impairs motivational drive, while serotonin imbalance contributes to mood disturbance and sleep disruption. Elevated glutamate levels, reflecting excitotoxicity, may damage neurons and perpetuate fatigue. These neurochemical shifts are consistent with findings in other post‑viral fatigue syndromes, reinforcing the role of neurotransmitter dysregulation.

7. Comparative Neurobiology

The neurobiological changes observed in COVID fatigue overlap with those in ME/CFS, Parkinson’s disease, and depression, including thalamic hypometabolism, basal ganglia dysfunction, and altered neurotransmission. However, the prominence of microvascular injury and persistent viral antigens appears unique to COVID, suggesting distinct mechanisms. Comparative neurobiology underscores both shared and novel pathways in fatigue syndromes.

Summary of Brain Nuclei Changes

COVID fatigue is characterized by pathological changes in brain nuclei, including thalamic hypometabolism, basal ganglia dysfunction, hypothalamic dysregulation, and brainstem injury. These changes disrupt network connectivity and neurotransmitter balance, producing a multidimensional syndrome of fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and autonomic imbalance. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies provide critical insight into the central mechanisms of fatigue, guiding future therapeutic strategies.

Sleep Disturbance in COVID Fatigue

1. Clinical Presentation

Sleep disturbance is among the most frequently reported symptoms in long‑COVID cohorts, often coexisting with fatigue and cognitive dysfunction. Patients describe insomnia, hypersomnia, fragmented sleep, non‑restorative sleep, and circadian rhythm disruption. These disturbances exacerbate fatigue, impair cognitive performance, and contribute to mood disorders. Surveys indicate that up to 60% of long‑COVID patients experience persistent sleep abnormalities, underscoring their central role in the syndrome.

2. Polysomnography Findings

Objective sleep studies reveal multiple abnormalities:

- Reduced slow‑wave sleep (SWS), impairing restorative processes.

- Decreased REM sleep, affecting memory consolidation and emotional regulation.

- Increased sleep latency and wake after sleep onset (WASO), consistent with insomnia.

- Altered circadian rhythm markers, including melatonin secretion patterns.

These findings suggest that COVID fatigue involves both macrostructural and microstructural sleep disruption, contributing to persistent exhaustion.

3. Neurobiological Mechanisms

Sleep disturbance in COVID fatigue reflects disruption of neural circuits regulating sleep and wakefulness:

- Hypothalamic injury: Inflammation and viral persistence in the suprachiasmatic nucleus impair circadian rhythm regulation.

- Brainstem dysfunction: Damage to nuclei controlling arousal (locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe) disrupts sleep architecture.

- Neurotransmitter imbalance: Altered serotonin and GABA signaling impair sleep initiation and maintenance.

- Cytokine effects: Elevated IL‑6 and TNF‑α interfere with sleep regulation, producing insomnia and non‑restorative sleep.

4. Interaction with Fatigue

Sleep disturbance and fatigue form a self‑reinforcing cycle. Poor sleep exacerbates fatigue, while fatigue impairs sleep quality. Post‑exertional malaise further disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to irregular sleep patterns. Cognitive dysfunction and mood disorders compound the cycle, creating a multidimensional syndrome resistant to simple interventions.

5. Comparative Sleep Pathology

The sleep abnormalities observed in COVID fatigue overlap with those in ME/CFS, depression, and PTSD. However, the prominence of circadian rhythm disruption and autonomic imbalance appears unique to COVID. Comparative studies highlight both shared and novel mechanisms, reinforcing the need for tailored therapeutic approaches.

6. Therapeutic Implications

Management of sleep disturbance in COVID fatigue requires a multifaceted approach:

- Behavioral interventions: Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT‑I), sleep hygiene, and pacing strategies.

- Pharmacologic therapies: Melatonin, sedative‑hypnotics, and antidepressants may provide symptomatic relief, though evidence is limited.

- Neuromodulation: Experimental approaches such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and vagal nerve stimulation show promise in restoring sleep architecture.

- Integrative therapies: Mindfulness, relaxation techniques, and chronotherapy may improve circadian alignment.

7. Prognosis

Sleep disturbance often persists for months to years, though some patients experience gradual improvement. Prognosis depends on the severity of underlying neuroinflammation and autonomic dysfunction. Persistent sleep abnormalities are associated with worse functional outcomes, highlighting the need for targeted interventions.

Summary of Sleep Disturbance

Sleep disturbance is a core feature of COVID fatigue, encompassing insomnia, hypersomnia, fragmented sleep, and circadian rhythm disruption. Neurobiological mechanisms include hypothalamic injury, brainstem dysfunction, neurotransmitter imbalance, and cytokine effects. Sleep abnormalities exacerbate fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, creating a self‑reinforcing cycle. Therapeutic strategies remain limited, underscoring the need for further research.

Treatments for COVID Fatigue

1. Symptomatic Management

At present, treatment for COVID fatigue remains largely symptomatic. Clinicians emphasize energy conservation and pacing strategies, encouraging patients to avoid overexertion that can trigger post‑exertional malaise. Structured rehabilitation programs focus on gentle aerobic activity, breathing exercises, and gradual reconditioning. However, graded exercise therapy remains controversial, as many patients experience worsening symptoms with exertion. Symptom‑guided pacing is therefore considered the safest approach.

2. Pharmacologic Therapies

Several pharmacologic interventions are under investigation:

- Anti‑inflammatory agents: Corticosteroids and biologics targeting IL‑6 and TNF‑α have been trialed, with mixed results. While some patients report improvement, risks of immunosuppression limit widespread use.

- Antivirals: Drugs such as remdesivir and molnupiravir are being studied for their potential to reduce viral persistence. Evidence remains preliminary.

- Antifibrotics: Agents like nintedanib and pirfenidone, used in pulmonary fibrosis, may mitigate lung scarring and improve oxygenation, indirectly reducing fatigue.

- Neuromodulators: Modafinil and methylphenidate, stimulants used in narcolepsy, have been prescribed off‑label to improve wakefulness. Results are variable, with some patients experiencing benefit and others reporting exacerbation of symptoms.

- Mitochondrial support: Supplements such as Coenzyme Q10, L‑carnitine, and nicotinamide riboside aim to enhance mitochondrial function. Small studies suggest modest improvements in energy.

3. Experimental Therapies

Novel approaches are being explored:

- Neuromodulation: Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and vagal nerve stimulation show promise in restoring autonomic balance and improving fatigue.

- Plasmapheresis: Removal of autoantibodies and inflammatory mediators has been trialed in small cohorts, with anecdotal improvement.

- Microclot clearance: Therapies targeting fibrinolysis, such as low‑dose anticoagulants, are under investigation to reduce microvascular obstruction.

- Stem cell therapy: Mesenchymal stem cells may modulate immune responses and promote tissue repair, though evidence is preliminary.

4. Integrative Approaches

Complementary therapies play a supportive role:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Helps patients manage the psychological burden of chronic fatigue, though it does not directly address biological mechanisms.

- Mindfulness and relaxation techniques: Reduce stress and improve sleep quality.

- Dietary interventions: Anti‑inflammatory diets and intermittent fasting are being explored for their potential to modulate immune responses.

- Acupuncture and yoga: Anecdotal reports suggest benefit in symptom management, though controlled trials are lacking.

5. Rehabilitation Programs

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs integrate physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychology, and nutrition. These programs emphasize individualized pacing, symptom monitoring, and gradual reintroduction of activity. Telemedicine platforms have expanded access to rehabilitation, allowing patients to receive support remotely.

6. Challenges in Treatment

Treatment of COVID fatigue is complicated by heterogeneity in symptom presentation and underlying mechanisms. What benefits one patient may worsen symptoms in another. The lack of standardized protocols underscores the need for personalized medicine approaches. Ongoing clinical trials aim to identify biomarkers that predict treatment response.

Summary of Treatments

Current treatment for COVID fatigue remains symptomatic, focusing on pacing and rehabilitation. Pharmacologic therapies, including anti‑inflammatories, antivirals, antifibrotics, neuromodulators, and mitochondrial support, show variable efficacy. Experimental approaches such as neuromodulation, plasmapheresis, and microclot clearance offer promise but require further validation. Integrative therapies provide supportive care, while multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs emphasize individualized management. The complexity of COVID fatigue necessitates personalized strategies and ongoing research.

Prognosis of COVID Fatigue

1. Recovery Trajectories

The prognosis of COVID fatigue varies widely. Longitudinal studies indicate that approximately 30–40% of patients experience gradual improvement within 12 months, while others remain symptomatic for years. Recovery trajectories are influenced by the severity of acute infection, comorbidities, and the presence of multi‑system involvement. Patients with mild initial illness may still develop chronic fatigue, underscoring that prognosis is not solely determined by acute severity.

2. Risk Factors for Chronicity

Several risk factors predict persistence of fatigue:

- Female sex: Women are disproportionately affected, possibly due to hormonal and immunological differences.

- Pre‑existing autoimmune or psychiatric conditions: These increase vulnerability to chronic fatigue.

- Severe acute illness: ICU admission and mechanical ventilation correlate with higher risk of long‑term fatigue.

- Persistent viral antigens and autoantibodies: Biomarkers of ongoing immune activation predict poor recovery.

3. Functional Outcomes

COVID fatigue significantly impairs functional outcomes. Many patients are unable to return to full employment, with some requiring disability support. Cognitive dysfunction and sleep disturbance compound physical fatigue, reducing quality of life. Functional impairment persists even in patients with normal laboratory and imaging findings, highlighting the disconnect between clinical symptoms and conventional diagnostics.

4. Socioeconomic Impact

The socioeconomic impact of COVID fatigue is substantial. Workforce participation declines, healthcare utilization increases, and disability claims rise. Families experience financial strain, while healthcare systems face increased demand for rehabilitation and supportive care. The burden of long‑COVID fatigue extends beyond individual patients, affecting communities and economies.

5. Prognostic Biomarkers

Research is ongoing to identify biomarkers that predict prognosis. Elevated cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α), microclot burden, and autoantibody profiles correlate with persistent fatigue. Neuroimaging markers, such as thalamic hypometabolism, may also predict chronicity. These biomarkers could guide personalized interventions and stratify patients for clinical trials.

6. Long‑Term Outlook

The long‑term outlook for COVID fatigue remains uncertain. Some patients recover fully, while others develop chronic syndromes resembling ME/CFS. The heterogeneity of outcomes reflects the complexity of underlying mechanisms. Continued research is essential to clarify prognosis and develop effective therapies.

Summary of Prognosis

COVID fatigue exhibits heterogeneous recovery trajectories, with some patients improving within a year and others developing chronic disability. Risk factors include female sex, pre‑existing conditions, severe acute illness, and persistent immune activation. Functional impairment and socioeconomic burden are substantial, underscoring the need for prognostic biomarkers and targeted interventions. The long‑term outlook remains uncertain, requiring ongoing research and clinical vigilance.

Conclusion

COVID fatigue represents one of the most pervasive and disabling sequelae of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection. Unlike ordinary tiredness, it is a multidimensional syndrome encompassing profound exhaustion, post‑exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, sleep disturbance, and autonomic imbalance. The evidence reviewed in this manuscript demonstrates that COVID fatigue arises from a complex interplay of mechanisms: viral persistence, immune dysregulation, microvascular injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and autoimmunity. These processes converge to disrupt energy metabolism, oxygen delivery, and neural signaling, producing a syndrome that resists simple explanations or interventions.

Genomic studies highlight host susceptibility factors, including HLA variants, ACE2 polymorphisms, and mitochondrial haplogroups, while viral mutations may modulate tissue tropism and persistence. Physiological investigations reveal systemic disruption across energy metabolism, cardiopulmonary function, neuroendocrine signaling, and sleep architecture. Pathological studies confirm muscle fiber atrophy, mitochondrial disruption, neuroinflammation, pulmonary fibrosis, and endothelial injury, with amyloid microclots emerging as a distinctive feature of COVID fatigue. Neuroimaging and neuropathological findings implicate thalamic, basal ganglia, hypothalamic, and brainstem nuclei, underscoring the central role of neural circuits in fatigue. Sleep disturbance further exacerbates symptoms, creating a self‑reinforcing cycle of exhaustion and cognitive impairment.

Treatment remains challenging. Current strategies emphasize pacing and rehabilitation, with pharmacologic and experimental therapies offering variable benefit. Neuromodulation, plasmapheresis, antifibrotics, and mitochondrial support represent promising avenues, but robust evidence is lacking. Integrative approaches provide supportive care, while multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs emphasize individualized management. Prognosis is heterogeneous: some patients recover within a year, while others develop chronic disability resembling ME/CFS. Risk factors include female sex, pre‑existing conditions, severe acute illness, and persistent immune activation. The socioeconomic burden is substantial, affecting workforce participation, healthcare utilization, and community resilience.

Future research must prioritize the identification of biomarkers that predict prognosis and guide personalized therapy. Systems biology approaches integrating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics will be essential to unravel the complexity of COVID fatigue. Clinical trials must evaluate targeted interventions, including antivirals, immunomodulators, antifibrotics, and neuromodulation. Policy initiatives should support rehabilitation programs, disability services, and workplace accommodations, recognizing the long‑term impact of COVID fatigue on individuals and societies.

In conclusion, COVID fatigue is a multifaceted syndrome that challenges conventional medical paradigms. Its etiology spans viral, immune, vascular, metabolic, and neural domains, while its clinical manifestations encompass physical, cognitive, and psychological dimensions. Addressing COVID fatigue requires an integrative approach that combines molecular research, clinical innovation, and policy support. Only through sustained effort across disciplines can we hope to alleviate the burden of fatigue and restore health to millions of survivors worldwide.

📚 Key References

- Predictors of non‑recovery from fatigue and cognitive deficits after SARS‑CoV‑2 infection — Lancet eClinicalMedicine (2024). Identifies risk factors for persistent fatigue and cognitive impairment.

- Global burden of persistent fatigue and cognitive clusters following COVID‑19 — JAMA (2022). Bayesian meta‑analysis of 54 studies, 1.2M individuals.

- Fatigue outcomes following COVID‑19: systematic review and meta‑analysis — BMJ Open (2023). Synthesizes prevalence and severity of fatigue.

- Long COVID Defined — NEJM (2024). National Academy of Medicine consensus on definitions and scope.

- Post‑infectious fatigue and circadian rhythm disruption in long‑COVID — Lancet eClinicalMedicine (2025). Explores overlap with ME/CFS and sleep disturbance.

- Long COVID and Sleep Disorders: Mechanisms, Brain Centers, and Therapeutic Advances — COVID‑19 Long Haul Foundation (2025). Detailed review of sleep disruption and hypothalamic involvement.

- Sleep and Long COVID — Review of Sleep Disturbances in PASC — Current Sleep Medicine Reports (2024). Clinical review of sleep pathology.

- Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Fatigue‑Dominant Long‑COVID — American Journal of Medicine (2024). Focused on fatigue‑dominant phenotype.

- Mechanisms of Long COVID and the Path Toward Therapeutics — Cell (2024). Comprehensive mechanistic review.