John Murphy, CEO, The COVID-19 Long-haul Foundation

Abstract

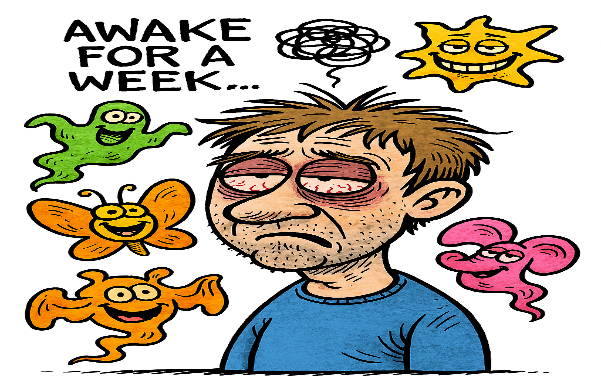

Sleep disturbances have emerged as one of the most persistent and debilitating manifestations of Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), commonly referred to as Long COVID. Affecting a substantial proportion of survivors, these disturbances encompass insomnia, hypersomnia, non-restorative sleep, and circadian rhythm dysregulation. This article synthesizes current evidence on the incidence, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and therapeutic approaches to sleep dysfunction in Long COVID, drawing from neuroimmunology, chronobiology, and sleep medicine.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has left a legacy not only of acute respiratory illness but of chronic, multisystem dysfunction in a subset of survivors. Among the constellation of symptoms reported in Long COVID, sleep disturbances stand out for their prevalence, complexity, and impact on quality of life. Unlike transient post-viral fatigue, these disturbances often persist for months, resist conventional treatment, and correlate with neuroinflammatory and autonomic dysregulation.

Sleep, once considered a passive state, is now understood as a dynamic neurophysiological process essential for immune regulation, cognitive function, and metabolic homeostasis. Its disruption in Long COVID is not merely symptomatic—it is pathognomonic of deeper systemic imbalance.

Incidence and Prevalence

Recent cohort studies estimate that up to 76% of Long COVID patients report sleep disturbances within six months of infection, with 28% continuing to experience symptoms at one year[^1]. The most common phenotypes include:

- Insomnia (difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep): 34.7%

- Hypersomnia (excessive daytime sleepiness): 9.3%

- Mixed sleep disorder (alternating insomnia and hypersomnia): 20.8%

- Circadian rhythm disruption: 6.9%

Risk factors include female sex, pre-existing anxiety or depression, high Area Deprivation Index (ADI), and hospitalization during acute infection[^2].

Etiology and Physiology

Neuroinflammation

SARS-CoV-2 triggers a cascade of inflammatory cytokines—IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β—that cross the blood-brain barrier and disrupt hypothalamic regulation of sleep[^3]. Postmortem studies reveal microglial activation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the brain’s master clock, and damage to orexin-producing neurons, which regulate wakefulness[^4].

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic imbalance, particularly postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), is prevalent in Long COVID and contributes to sleep fragmentation. Reduced parasympathetic tone and elevated heart rate variability (HRV) impair sleep onset and maintenance[^5].

Mitochondrial Impairment

Hypothalamic neurons exhibit reduced ATP production, compromising their ability to sustain sleep architecture. This mitochondrial dysfunction correlates with central fatigue and non-restorative sleep[^6].

Cortisol Dysregulation

Delayed evening cortisol peaks interfere with melatonin synthesis, leading to circadian misalignment. Salivary cortisol studies show blunted diurnal variation in Long COVID patients with insomnia[^7].

Glymphatic System Impairment

Microvascular damage and endothelial dysfunction impair cerebrospinal fluid clearance during sleep, leading to accumulation of neurotoxins and exacerbation of brain fog[^8].

Pathology

Neuropathological findings in Long COVID include:

- Hypothalamic inflammation: affecting SCN and orexin neurons

- Brainstem dysfunction: particularly in the locus coeruleus, which modulates REM sleep

- Glymphatic stasis: reducing clearance of β-amyloid and other metabolites

These changes mirror those seen in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and post-viral encephalopathy, suggesting a shared pathophysiological substrate.

Clinical Manifestations

Sleep disturbances in Long COVID present with:

- Insomnia: prolonged sleep latency, frequent awakenings, early morning arousal

- Hypersomnia: excessive sleep duration, unrefreshing sleep, daytime sleep episodes

- Circadian disruption: delayed sleep phase, irregular sleep-wake cycles

- Associated symptoms: fatigue, cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”), mood instability

Polysomnography often reveals reduced slow-wave sleep, increased sleep fragmentation, and altered REM latency[^9].

Consequences

The impact of sleep dysfunction in Long COVID is profound:

- Cognitive impairment: memory deficits, slowed processing speed

- Mood disorders: depression, anxiety, irritability

- Cardiometabolic risk: insulin resistance, hypertension, weight gain

- Functional decline: reduced productivity, social withdrawal, increased healthcare utilization

Sleep disturbances also correlate with higher levels of inflammatory markers and poorer recovery trajectories[^10].

Treatment Strategies

Behavioral and Chronobiological Interventions

- Morning light exposure: resets circadian rhythm, lowers evening cortisol

- Fixed wake-up time: anchors sleep-wake cycle

- Digital curfew: reduces pre-sleep arousal

- Diaphragmatic breathing: improves HRV and sleep onset

Pharmacologic Therapies

| Agent | Mechanism | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Melatonin (2–8 mg) | Circadian entrainment | Insomnia, delayed sleep phase |

| Modafinil/Solriamfetol | Wakefulness promotion | Hypersomnia |

| Low-dose naltrexone | Immune modulation | Sleep depth, fatigue |

| Prazosin | Alpha-1 antagonist | Nightmares, fragmented sleep |

| CBT-I | Cognitive restructuring | First-line for insomnia |

RECOVER-SLEEP Trials

NIH-funded trials are evaluating combinations of melatonin, light therapy, modafinil, and pacing strategies. Preliminary results show improved sleep latency and reduced daytime sleepiness[^11].

Conclusion

Sleep disturbances in Long COVID are not epiphenomena—they are central expressions of systemic dysregulation. Their persistence reflects neuroimmune imbalance, autonomic dysfunction, and circadian disruption. Effective management requires phenotype-specific interventions, interdisciplinary collaboration, and ongoing research into the neurobiology of post-viral syndromes.

Footnotes

[^1]: Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. [^2]: Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259–264. [^3]: Mehandru S, Merad M. Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID. Nat Immunol. 2022;23(2):194–202. [^4]: Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure. Nature. 2022;604(7907):697–707. [^5]: Raj SR, Arnold AC, Barboi A, et al. Long COVID and POTS: Is Dysautonomia to Blame? Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(6):941–947. [^6]: Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(9):895–906. [^7]: Mazza MG, Palladini M, De Lorenzo R, et al. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: Effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three-month follow-up. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:138–147. [^8]: Lee MH, Perl DP, Nair G, et al. Microvascular injury in the brains of patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):481–483. [^9]: Altena E, Baglioni C, Espie CA, et al. Dealing with sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020;70:12–18. [^10]: Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, et al. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236,379 survivors of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416–427. [^11]: NIH RECOVER Initiative. RECOVER-SLEEP Trial Protocol. https://recovercovid.org