Long COVID-19: a Four-Year prospective cohort study of risk factors, recovery, and quality of life

Sanaa M. Kamal, Mohammed S. Al Qahtani, Ali Al Aseeri, et. al.

Abstract

Purpose

Long COVID-19 is a growing public health concern, but its long-term burden and predictors remain underexplored, particularly in underrepresented populations.

Methods

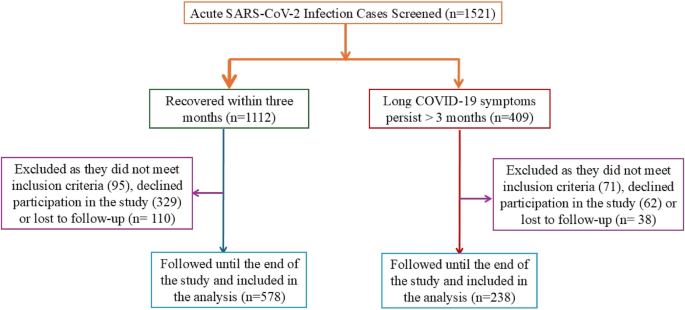

This four-year prospective cohort study was conducted in Saudi Arabia, enrolling adults with confirmed acute COVID-19 from multiple affiliated healthcare centers between March 2020 and March 2024. Of 1,521 screened patients, 816 were enrolled and followed for up to four years (median: 24 months). Per WHO criteria, participants were classified as having long COVID-19 (n = 238) or resolved infection (n = 578). Demographics, comorbidities, vaccination, reinfection, and acute illness severity were recorded. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using SF-36 and EQ-5D-5 L. Logistic regression identified predictors of long COVID-19, and Cox proportional hazards models evaluated time to recovery.

Results

Fatigue (57.1%), post-exertional malaise (45.8%), cough (41.2%), and cognitive dysfunction (30.7%) were the most common persistent symptoms. Female sex (adjusted OR 11.11; 95% CI: 4.48–26.24) and diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR 14.3; 95% CI: 7.0–29.4) independently predicted long COVID-19. Delayed recovery was associated with female sex (aHR 3.36; 95% CI: 1.85–6.10), diabetes (aHR 1.57; 95% CI: 1.00–2.46), reinfection (aHR 1.86; 95% CI: 1.05–3.29), and hospitalization (aHR 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.16). HRQoL scores remained significantly lower at 6 and 12 months. In the long COVID-19 group, 38.7% of patients normally resumed work within 12 months, compared to 82.3% in the resolved COVID-19 group.

Conclusions

Nearly 29% of post-acute COVID-19 patients developed long COVID-19 in this Middle Eastern cohort. Female sex, diabetes, reinfection, and hospitalization predicted delayed recovery. Persistent symptoms and impaired HRQoL highlight the need for early risk stratification and structured post-COVID care.

View this article’s peer review reports

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in an unprecedented global health crisis, with over 778 million confirmed cases reported worldwide as of March 2025 [1]. Although most individuals recover from the acute phase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, a significant proportion develop persistent or delayed symptoms—a condition now referred to as long COVID-19, post-COVID-19 condition (PCC), or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) [2, 3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines long COVID-19 as a condition occurring within three months of infection onset, with symptoms lasting at least two months and not attributable to alternative diagnoses [4].

Long COVID-19 has been associated with substantial functional and socioeconomic burden across all age groups and levels of disease severity, regardless of vaccination status. Reported prevalence varies widely—from 10–50%—depending on the population studied and the criteria used [5, 6]. Common manifestations include fatigue, dyspnea, thrombotic events, cardiovascular and autonomic dysfunction, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cognitive impairment [7, 8]. The cumulative burden of long-COVID-19 includes increased healthcare utilization, prolonged disability, and reduced workforce participation.

The underlying pathophysiology of long COVID-19 remains incompletely understood. Hypothesized mechanisms include immune dysregulation, persistent viral reservoirs, endothelial injury, gut dysbiosis, and post-viral autoimmunity [9,10,11]. While vaccination is effective in preventing severe COVID-19 and reducing mortality [12, 13], evidence regarding its role in mitigating long COVID-19 is mixed. Some studies suggest a protective effect, particularly with pre-infection vaccination, while others show limited or inconsistent benefits [14, 15].

Despite the growing body of research [16, 17], critical knowledge gaps remain, especially in underrepresented populations. There is a lack of longitudinal data from the Middle East, and few studies have comprehensively examined the roles of reinfection, vaccination, comorbidities, and acute illness severity in the development and persistence of long-COVID-19 over extended follow-up.

In this prospective cohort study, we aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated with long COVID-19, characterize its clinical manifestations, and evaluate its long-term impact on functional recovery and quality of life. We also assessed the influence of reinfection and vaccination over a four-year follow-up period.

Methods

Study design and setting

This prospective longitudinal cohort study was conducted between March 2020 and March 2024 in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Patients were recruited from Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University Hospital, its affiliated vaccination center, King Khalid Hospital, and associated healthcare facilities.

Enrollment was conducted continuously throughout the four-year study period. Eligible participants were those with RT-PCR–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who provided written informed consent for long-term follow-up.

The study cohort was stratified into two groups: Long COVID-19 group: patients with symptoms persisting ≥ 3 months post-infection, and resolved group: patients with complete resolution of symptoms within 3 months.

To evaluate temporal trends, participants were categorized based on their enrollment period: March 2020–March 2021, March 2021–March 2022, March 2022–March 2023, and March 2023–March 2024.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University (IRB No. SCBR-102/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Participants

Adults aged ≥ 18 years with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: Severe systemic autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus); active malignancy; neurodegenerative or severe psychiatric disorders; pregnancy; and inability to complete long-term follow-up. Patients with stable, controlled organ-specific autoimmune conditions (e.g., autoimmune thyroiditis) were not excluded.

Long COVID-19 was defined according to WHO criteria as the persistence or recurrence of one or more symptoms ≥ 3 months after the onset of acute infection, lasting for at least 2 months, and not explained by alternative diagnoses.

Data collection and clinical assessment

Baseline data included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, BMI, smoking status, hospitalization or ICU admission, and vaccination and reinfection status. Data were collected using structured interviews and verified against electronic medical records. Symptom burden was systematically recorded at baseline and each scheduled follow-up visit [18].

Quality of life assessment

HRQoL was evaluated using the SF-36 v2 and EQ-5D-5 L questionnaires, administered in Arabic or English depending on participant preference. A subgroup analysis confirmed no significant difference in results between the two language versions [19,20,21,22]. The SF-36 v2 evaluates eight health domains and generates composite physical and mental health summary scores. The EQ-5D-5 L evaluates five domains and includes a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state).

Vaccination status

The vaccination status was categorized as fully vaccinated (completion of the primary series plus at least one booster before infection), partially vaccinated (incomplete primary series), or unvaccinated (no vaccination before infection).

Follow-up assessments

Participants were scheduled for follow-up visits every 3 months during the first year and every 6 months thereafter, for up to 4 years. Each visit included a structured symptom review, physical examination, and HRQoL assessments. Unscheduled visits were permitted for worsening symptoms or suspected reinfection. Retention was optimized through telephone reminders and transportation assistance.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the development of long COVID-19, defined according to WHO criteria as the persistence or recurrence of one or more symptoms ≥ 3 months after acute infection, lasting for at least 2 months, and not explained by alternative diagnoses.

The secondary outcomes included: Symptom burden and resolution trajectories over time; HRQoL scores (SF-36 v2 and EQ-5D-5 L); time to symptom recovery; and return to work, assessed at 12 months post-infection.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software, version 4.4.3. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with approximately normal distributions were presented as means with standard deviations (SD), whereas non-normally distributed variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons were conducted using independent t-tests for normally distributed variables, Mann–Whitney U tests for skewed data, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data. Where applicable, Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons to reduce the risk of type I error.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of developing long COVID-19. Predictor variables were selected based on clinical relevance and statistical significance in univariate analysis. Specifically, variables with a P value < 0.20 in the univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model using a stepwise backward elimination approach. The final model included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hospitalization (as a marker of acute illness severity), reinfection, and chronic pulmonary disease. Model calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs), all of which were < 2.5, indicating no significant collinearity. The discriminative ability of the final model was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (C-statistic), which was 0.81, indicating good predictive performance.

Missing data ranged from 0.9 to 7.4% across study variables. Complete-case analysis was used for variables with < 5% missing data. For variables with ≥ 5% missing values (BMI: 7.4%, vaccination status: 5.2%, EQ-5D: 6.8%), we employed multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) under the assumption of missing-at-random. Twenty imputed datasets were generated, and the results were pooled according to Rubin’s rules. Sensitivity analyses comparing complete-case and imputed datasets yielded consistent results for key predictors, particularly for female sex and diabetes mellitus, confirming the robustness of the findings.

Using Kaplan- Meier survival analysis, we also assessed the time needed to resolve symptoms among patients with long COVID-19. Differences between subgroups (e.g., sex, reinfection, hospitalization, age group, and chronic pulmonary disease) were evaluated using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of delayed recovery, incorporating the same covariates as the logistic regression model. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by inspecting Schoenfeld residuals and graphical diagnostics, which confirmed model validity. All statistical tests were two-sided; a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

Between March 2020 and March 2024, 1,521 patients with RT-PCR-confirmed acute SARS-CoV-2 infection were screened. Of these, 816 met eligibility criteria, consented to long-term follow-up, and were enrolled in the study. Among these, 238 participants (29.2%) developed symptoms persisting ≥ 3 months and fulfilled the WHO definition of long COVID-19, while 578 (70.8%) experienced complete symptom resolution within 3 months (Fig. 1). Participants represented a diverse population, including Saudis (53.6%), Egyptians (12.6%), Indians (9.6%), Filipinos (9.2%), Pakistanis (5.4%), Sudanese (6.3%), Jordanians (1.8%), and North Africans (1.5%).

Enrollment was distributed across four time intervals as follows: March 2020–March 2021 (23.3%), March 2021–March 2022 (26.5%), March 2022–March 2023 (28.6%), and March 2023–March 2024 (21.6%).(Supplementary Fig. 3 A) The median follow-up duration was 24 months. The assessment for long COVID-19 outcomes adhered strictly to the WHO definition, which requires symptoms to persist or reappear ≥ 3 months after acute infection. Of the 816 participants, 100% completed ≥ 6 months of follow-up, 84.9% completed ≥ 12 months, 64.2% completed ≥ 24 months, 41.5% completed ≥ 36 months, and 19.8% completed ≥ 48 months. The overall dropout rate was 7.1%, primarily due to relocation.When stratified by enrollment period, the prevalence of long COVID-19 declined progressively: 34.7% (2020–2021), 30.1% (2021–2022), 26.8% (2022–2023), and 23.2% (2023–2024). (Supplementary Fig. 3B)

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

Patients with long COVID-19 were significantly older than those in the resolved group (mean age: 47.05 ± 16.26 vs. 39.25 ± 12.74 years, P <.001). A higher proportion were female (63.0% vs. 49.6%, P <.001), and comorbid conditions were more frequent, including diabetes mellitus (40.3% vs. 9.9%), hypertension (24.0% vs. 8.1%), dyslipidemia (20.6% vs. 7.4%), cardiac disease (15.6% vs. 3.6%), chronic pulmonary disease (14.3% vs. 1.6%), and chronic renal disease (12.2% vs. 1.4%) (all P <.001) (Table 1).Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients with long COVID-19 vs. Resolved COVID-19

Hospitalization during the acute phase occurred more often among long COVID-19 patients (20.6% vs. 2.8%, P <.001), as did severe or critical acute illness (37.4% vs. 9.3%, P <.001). Reinfection was also significantly more prevalent in the long COVID-19 group (34.9% vs. 12.8%, P <.001).

Concerning vaccination, patients who developed long COVID-19 were significantly less likely to have been fully vaccinated before infection (29.8% vs. 54.3%) and more likely to be partially vaccinated (43.3% vs. 26.1%) or unvaccinated (26.9% vs. 19.6%) (P <.001).

Clinical manifestations of Long COVID-19

The most frequently reported symptoms among patients with long COVID-19 were fatigue (57.1%), post-exertional malaise (45.8%), cough (41.2%), cognitive dysfunction (30.7%), dyspnea (24.8%), chest pain or tightness (23.9%), and headaches (20.6%) (Table 2). Neurological, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal symptoms were also reported with higher prevalence in the long COVID-19 group compared to the resolved group (all P <.001).Table 2 Prevalence of symptoms and signs in patients with long COVID-19 compared to those with resolved infection (Point prevalence at 6 months from enrollment)

Symptoms such as cranial nerve involvement (5.0%), vocal cord paralysis (2.1%), and phobic or anxiety-related presentations (3.8%) were rare but notably more frequent in the long COVID-19 group. Sleep disturbances and memory impairment were common neurocognitive complaints.

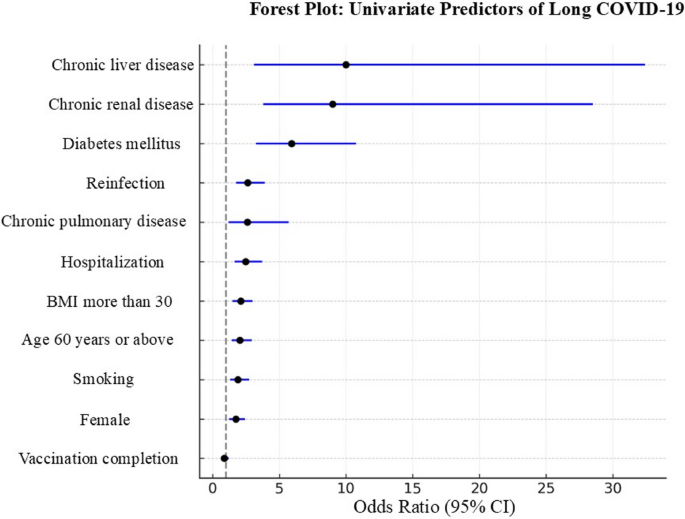

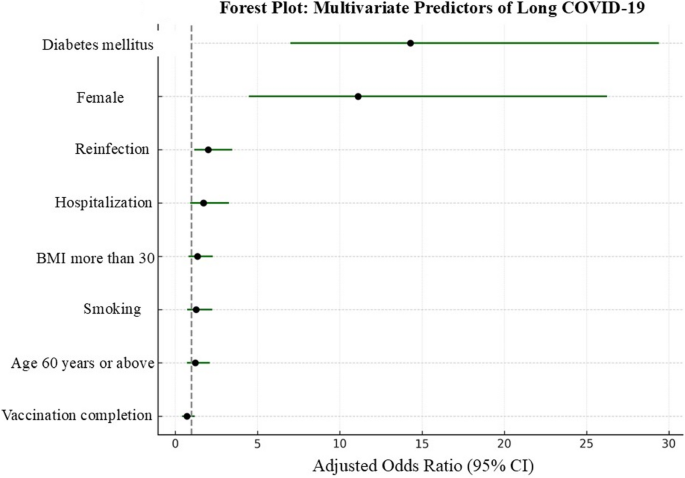

Predictors of long COVID-19

In univariate analysis, older age (≥ 60 years), female sex, smoking, obesity (BMI ≥ 30), hospitalization, reinfection, and multiple comorbidities were significantly associated with long COVID-19 (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 2). In the multivariable logistic regression model, female sex (adjusted OR 11.11; 95% CI: 4.48–26.24; P <.001) and diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR 14.3; 95% CI: 7.0–29.4; P <.001) emerged as independent predictors of long COVID-19 (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 2).

Other variables (e.g., age, BMI, smoking, and hospitalization) lost statistical significance after adjustment, likely due to collinearity or confounding with stronger predictors. Model performance was robust, with good calibration (Hosmer–Lemeshow P =.74) and strong discrimination (C-statistic = 0.81).

Time to recovery and factors influencing recovery

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated significantly prolonged time to symptom resolution among the long COVID-19 group compared to those with resolved infection (log-rank P <.001; Supplementary Fig. 1 A).

Stratified analysis revealed that female sex, diabetes mellitus, reinfection, and hospitalization during acute illness were significantly associated with delayed recovery. Age ≥ 60 years and incomplete vaccination showed non-significant trends toward slower recovery. Exploratory interaction analyses showed no significant effect modification by vaccination status or age: the association between diabetes and long COVID-19 risk was consistent across vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, and female sex remained an independent risk factor across all age groups (data not shown).

In the Cox proportional hazards model, female sex (aHR 3.36; 95% CI: 1.85–6.10; P <.001), diabetes mellitus (aHR 1.57; 95% CI: 1.00–2.46; P =.048), reinfection (aHR 1.86; 95% CI: 1.05–3.29; P =.033), and hospitalization (aHR 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.16; P =.026) were independently associated with delayed recovery. The proportional hazards assumption was met, and model diagnostics confirmed good fit (Supplementary Table 3).

Symptom-specific recovery patterns

Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by symptom type (Supplementary Fig. 1B) demonstrated variability in resolution times. Fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disturbances exhibited the most extended median durations, persisting for > 32 weeks in many cases. In contrast, cough and anosmia typically resolved within 8–12 weeks. Kaplan–Meier curves confirmed that neurocognitive and fatigue-related symptoms persisted significantly longer than cardiopulmonary or gastrointestinal complaints, suggesting differing underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Quality of life and functional outcomes

Patients with long COVID-19 reported significantly lower HRQoL scores on the SF-36 and EQ-5D-5 L instruments at 6 and 12 months (all P <.001), with impairments across all domains.

Work resumption was assessed using categorical and continuous measures. Work resumption by 12 months post-infection was significantly lower in the long COVID-19 group (38.7%) compared to the resolved group (82.3%) (P <.001). Specifically, 38.7% of long COVID-19 patients resumed work within 12 months compared to 82.3% in the resolved group, and the mean time to return to work was significantly longer in the long COVID-19 group (31.2 weeks vs. 9.4 weeks; P <.001) (Supplementary Table 4).

Survey language (Arabic vs. English) did not significantly affect SF-36 or EQ-5D responses in subgroup analyses, suggesting that the validated translations used were reliable for both populations.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of 816 patients followed up to four years after acute COVID-19, approximately 29% met the WHO criteria for long COVID-19. This finding is consistent with the higher prevalence estimates reported globally and highlights the long-term burden of post-acute COVID-19 symptoms. Our study offers several vital contributions: it provides one of the longest prospective follow-ups of long COVID-19 to date. It contributes new longitudinal insights by following patients for up to four years, highlighting the sustained burden of long COVID-19 not only in an underrepresented Middle Eastern and Asian population. Additionally, by evaluating the effects of reinfection and varying vaccination statuses on recovery, we provide a more nuanced understanding of long COVID-19 risk factors and recovery patterns, which may inform post-COVID care strategies in similar populations.

Our cohort had a relatively young average age (mean 41.3 years), reflecting the underlying population demographics and workforce composition of the study region, which is characterized by a predominance of younger, working-age adults. This demographic profile may partially explain differences in symptom prevalence and recovery trajectories compared to older European cohorts, where age-related comorbidities are more common.

Our cohort’s most frequently reported symptoms included fatigue, post-exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, and respiratory complaints. These findings mirror those reported by Sigfrid et al. and Walker et al., who similarly identified fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms as dominant and persistent features of long COVID-19 [23, 24]. In our cohort, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction persisted for over 32 weeks in some individuals, while symptoms such as cough and anosmia resolved more quickly. Our analysis adds to the existing literature by demonstrating that diabetes mellitus and female sex were independently associated with developing long-COVID-19. These associations are consistent with previously published findings by Xie et al. [25], Rathmann et al. [26], Liu et al. [27], and Ayoubkhani et al. [28], who have collectively reported that metabolic dysregulation and sex-specific immune responses may predispose individuals to prolonged post-acute symptoms. Xie et al. [25] also reported an increased incidence of new-onset diabetes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, further emphasizing the bidirectional relationship between COVID-19 and glucose metabolism.

Neurological manifestations in our cohort extended beyond cognitive complaints and included cranial nerve involvement and isolated unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Although rare, uncommon sequelae are increasingly reported and may reflect neuroinflammatory or neurovascular mechanisms in the aftermath of COVID-19 infection [29, 30]. Our findings highlight the need for tailored rehabilitation strategies for symptom-specific recovery trajectories.

In the multivariable analysis, female sex and diabetes mellitus emerged as the only independent predictors of long COVID-19. The association between female sex and increased risk is consistent with previous studies and may reflect sex-specific differences in immune function, hormonal regulation, or healthcare-seeking behavior [25, 26]. Interestingly, the effect size for female sex was modest in the univariate analysis but markedly increased after adjustment (aOR 11.11). This finding likely reflects confounding by comorbidities such as diabetes and hospitalization, which were more common among males in our cohort and may have masked the independent effect of sex in the unadjusted model. After controlling for these factors, the strong independent association of female sex with long COVID became evident, supporting a potential biological or immune-mediated mechanism rather than differences solely attributable to comorbidity profiles. The strong effect size observed for diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR 14.3) underscores the possible role of metabolic dysregulation in impairing post-viral recovery mechanisms [27, 28].

Although several variables, such as advanced age, smoking, elevated BMI, and acute illness severity, were significantly associated with long COVID-19 in the univariate analysis, they remained insignificant in the multivariate model. This attenuation of significance likely reflects collinearity or confounding by stronger predictors, notably female sex and diabetes mellitus, which emerged as independent risk factors. For instance, hospitalization and illness severity may function more as mediators of risk rather than direct predictors, with their effects partially captured by comorbidities such as diabetes. Comorbidities such as chronic renal and pulmonary diseases, which exhibited high odds ratios in the univariate analysis, lost statistical significance after adjustment, reflecting confounding by age and cardiometabolic conditions and potential mediation through acute illness severity. Exploratory interaction analyses between sex and age showed no significant interaction, confirming that female sex remained an independent risk factor across all age groups. These findings are consistent with other studies [26,27,28] and underscore the complexity of modeling long COVID-19 risk, where interdependent clinical factors can mask individual effects in multivariable analyses.

Importantly, risk factors for developing long COVID-19 did not completely overlap with those for prolonged recovery once long COVID-19 was established. Using a Cox proportional hazards model, we found that female sex, diabetes mellitus, reinfection, and hospitalization during acute illness were independently associated with delayed recovery, whereas age ≥ 60 years and chronic pulmonary disease were insignificant after adjustment. These differences likely reflect distinct mechanisms: while female sex and diabetes consistently influence both susceptibility and recovery, hospitalization may act as a marker of severe acute organ injury, prolonging recovery rather than increasing initial risk. Similarly, reinfection may exacerbate symptoms or trigger relapses in patients already affected by long COVID, but its role in initiating long COVID appears limited after adjustment for other risk factors. These observations emphasize that risk factors for developing long COVID and those sustaining prolonged symptoms overlap but are not identical, representing different stages of disease pathophysiology.

Vaccination status showed a protective trend in the time-to-recovery model. However, it did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to variability in timing, vaccine type, or waning immunity, as suggested in prior studies [14, 15]. The declining prevalence observed across enrollment periods may reflect increased vaccine coverage and/or reduced virulence of later SARS-CoV-2 variants, consistent with emerging global trends. Although variant-specific genomic data were unavailable in all our cohort patients, we stratified participants into four enrollment periods to approximate the impact of evolving epidemiological and immunological factors. Our data cannot directly attribute causality to specific variants; however, the trend parallels published findings showing a reduced risk of long COVID with vaccination and infections occurring during Omicron-dominant periods.

Our study also evaluated functional and quality-of-life outcomes using the SF-36 and EQ-5D-5 L instruments. Patients with long COVID-19 had significantly lower scores across all domains at 6 and 12 months, and only 38.7% had returned to work within one year, compared to 82.3% in the resolved group. These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting persistent fatigue and reduced quality of life in long COVID-19 survivors [10, 17]. Such substantial functional limitations warrant systematically integrating post-COVID care services into existing healthcare frameworks. Fatigue, neurocognitive impairment, and psychological distress appeared to be particularly limiting, suggesting that multidisciplinary rehabilitation, encompassing physical, psychological, and occupational support, may be essential for long-term recovery.

Our estimated long COVID-19 prevalence of 29.2% should be interpreted in the context of a hospital-affiliated cohort that included a high proportion of patients with pre-existing comorbidities and more severe acute infections, including hospitalized cases. Consequently, this prevalence may overestimate the burden observed in community-based or younger, healthier populations. Indeed, several population-based studies have reported lower prevalence rates, reflecting differences in baseline health status, healthcare-seeking behavior, and case ascertainment. Our findings, however, are particularly relevant for healthcare systems serving similar high-risk populations, such as tertiary care centers and regions with a high burden of metabolic comorbidities.

Although our findings support early identification of individuals at higher risk, such as women and those with diabetes, we acknowledge that our study is observational and cannot establish causality. While these risk factors may serve as useful markers for follow-up, interventional studies are required to determine whether tailored interventions improve long-term outcomes in these subgroups. We also explored potential interactions (e.g., between diabetes and vaccination or sex and age), but no significant modifying effects were observed. The stability of these associations across vaccination and age subgroups further supports the robustness of our findings and aligns with other long COVID-19 cohorts, where female sex and diabetes have consistently emerged as independent risk factors regardless of demographic or immunological strata [31, 32].

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although symptom and QoL assessments were conducted prospectively, they relied partly on self-report and may be influenced by recall or response biases. Second, we did not perform formal neuropsychological testing to objectively quantify cognitive deficits, which may have led to underestimation or misclassification of neurocognitive symptoms. Future studies should incorporate comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations to better represent long-term cognitive sequelae, as demonstrated in some studies using standardized cognitive assessment [33, 34]. Third, we did not collect biomarkers or virologic data to explore mechanistic pathways (e.g., autoimmunity and persistent viral load), although such investigations are ongoing in parallel studies. Fourth, while enrollment spanned four years, allowing long-term insight, temporal shifts in circulating variants, vaccination policy, and public health interventions may have introduced heterogeneity. Lastly, the study was conducted in a single national setting, which may limit generalizability to other healthcare systems.

In conclusion, this study provides one of the longest and most comprehensive prospective evaluations of long COVID-19 to date in the Middle East. Nearly one-third of acute COVID-19 patients in our cohort developed long-term symptoms, most commonly fatigue and cognitive dysfunction. Female sex and diabetes mellitus were independent predictors, while reinfection and hospitalization were associated with delayed recovery. The observed prevalence of 29.2% aligns with the upper range of global estimates. Importantly, this burden persists despite Saudi Arabia’s early and efficient public health response, which included nationwide screening from the onset of the pandemic and initiation of vaccination programs as early as December 2020, with substantial efforts to ensure high vaccination completion rates.

Given the young population structure and high prevalence of diabetes in the Kingdom, these findings underscore the need to integrate post-COVID care into national health systems, establish multidisciplinary long COVID clinics, and develop population-specific risk stratification tools. Our findings support early identification of at-risk individuals—particularly those with diabetes and female patients—to enable timely interventions such as structured rehabilitation programs, cognitive behavioral therapy, glycemic control optimization, mental health support, and close clinical monitoring through post-COVID care pathways. However, these observational findings do not establish causality; prospective interventional trials are needed to determine whether risk-specific management strategies can modify long COVID-19 outcomes.