Story by Shreyas Teegala and Simar Baja

Experts say those patients at the highest risk of developing severe illness should get vaccinated.© Andriy Onufriyenko, Moment via Getty Images

Since the first Covid-19 vaccines were authorized in December 2020, more than 672 million doses have been administered in the United States. For years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has broadly recommended up-to-date vaccination, which more recently includes Covid shots, for nearly all age groups to reduce the risk of severe disease and death.

Vaccine policy is usually decided by a group of outside experts—the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which holds a public meeting to review vaccine data, take questions, vote on recommendations, and then advise the director of the CDC accordingly.

But, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. departed from this protocol via a post on X. Two weeks before the committee was scheduled to meet, Kennedy announced that two groups, specifically pregnant women and healthy children, would no longer be recommended to receive Covid vaccines. He did not mention recommendations for other populations.

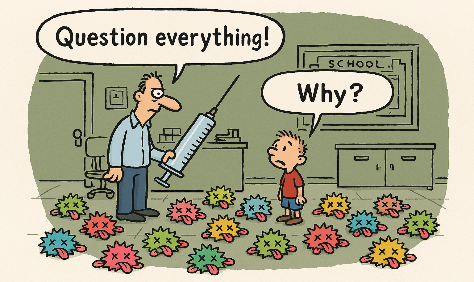

The move was unprecedented and controversial.

The landscape was further muddled by the CDC announcing that the Covid-19 vaccines would remain on the childhood immunization schedule, contradicting RFK Jr.’s decree. “We’re in a little bit of uncharted waters,” says Michelle Fiscus, the chief medical officer of the nonprofit Association of Immunization Managers.Related video: What are mRNA vaccines? (STAT News Video – Video)

Loaded: 9.82%Play

Current Time 0:00

/

Duration 2:02Quality SettingsCaptionsFullscreen

What are mRNA vaccines?Unmute

0

And what started as a pre-emptive sidestep escalated to an elimination and then replacement. On Monday, RFK Jr. fired all 17 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, claiming the panel needed to be reconstituted to avoid conflicts of interest that he says preclude sufficient scrutiny of vaccines. On Wednesday, he named eight new members to the committee, including four, as the New York Times reported, “who have spoken out against vaccination in some way.” The changes add to the uncertainty about how immunization policy will be developed and whether the burden of paying for vaccines will shift more to patients, rather than insurers.

These recent developments have left many people confused about the updated Covid-19 vaccines and who should be taking them. So we consulted vaccine and public health experts to help make sense of the recent changes.

What’s the difference between a booster and an updated vaccine?

When Covid-19 vaccines first became available, they were administered as one or two doses, protecting against severe illness and death. But immunity wanes over time, Fiscus says, so booster vaccines, or additional doses of the primary series, were introduced to maintain protection—even if only in the short term.

As the pandemic progressed, new variants like Delta and Omicron emerged and evaded vaccine protection, prompting the need for new targeted formulations, she continues. So repeated doses of the original vaccine, or boosters, were replaced with updated vaccines — new compositions that better match circulating viral strains.

So when it comes to the latest recommendations, “we’re not talking about boosters anymore, Fiscus says. “We’re talking about new vaccines.”

Who should get the updated Covid-19 vaccine?

Simply put, those at the highest risk of developing severe illness.

Adults over age 65 and people with compromised immune systems are clear examples, says Anil Makam, a hospital medicine physician at the University of California, San Francisco—because they’re more likely to be hospitalized and die of Covid-19.

So the CDC’s recent choice to drop healthy pregnant women from its recommendations was confusing. “Pregnancy is probably the highest dynamic risk condition,” says Jeremy Faust, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, because it puts otherwise healthy women in vulnerable positions

This is because pregnancy suppresses the expecting mother’s immune system, says Ofer Levy, a pediatrician and director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, so that it doesn’t attack the fetus as a foreign pathogen. The updated vaccines can thus help pregnant women stay protected.

The Covid-19 vaccines can also protect the newborn—one of the highest-risk groups for hospitalization—since taking a dose during pregnancy confers maternal antibodies to the fetus, Faust says. Because data on the safety of vaccinating children under 6 months isn’t available, vaccinating pregnant women is the best way to protect babies over that period, he continues.

But some experts feel these benefits will likely be modest. For example, since most pregnant women have already received the primary vaccine series, they will still have Covid-19 antibodies in their blood and be able to transfer some to their fetus via the placenta or breast milk. So the real question, Makam says, is what additional protection does another dose provide beyond the immunity they already have? While the evidence on the marginal benefits of updated vaccines isn’t definitive, Faust says they still make sense to help prevent severe disease complications for mother and child. He reminds that “the maternal mortality during Covid was extraordinarily terrible, and it’s gotten a lot better due to vaccines.”

Do healthy people need an updated vaccine?

The general public health recommendation: probably not. “Higher risk and older populations should stay up to date on Covid vaccines,” Faust says. “Everyone else may.”

It comes back to the same question about extra doses: “If you’re getting one every cycle, the benefits are probably minimally advantageous and short-lived,” Makam says.

But while the decision to get a vaccine is binary, informed decisions exist on a spectrum. “I am 59 years old, so I’m not yet considered elderly. But I’m at higher risk than somebody who’s 20,” Levy says. “Where do you draw that line?”

As such, the choice to receive an updated vaccine should be made with a trusted health care provider, who can weigh medical history, local Covid-19 trends and household circumstances, he continues. Physicians sometimes call this process “shared decision-making.”

The same logic generally holds for children. Since they have the least exposure to the virus, they definitely should get vaccinated for Covid-19 if they haven’t before, Faust says. But for those who are healthy and have already gotten the original series, the updated vaccine may only offer limited benefits, so further vaccination should be considered on a case-by-case basis by pediatricians and families.

Still, some caution is warranted, especially for adolescent boys and young men, the one group with a consistently observed—albeit small—risk of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, Makam says. Given this drawback and the likely minimal benefits, he suggests that an updated vaccine may not be worth it for this group. That said, the landscape is shifting: The risk of myocarditis has decreased significantly with updated vaccines, Faust notes, offering reassurance as families and clinicians weigh their options.

To summarize, for healthy people already vaccinated by the primary series, an updated dose may or may not be necessary, but this decision should come from a conversation between families and their providers, according to Levy.

Should anyone avoid the updated vaccine?

People who’ve had myocarditis shortly after a previous dose or have faced multisystem inflammatory syndrome, a rare Covid-19 complication, should avoid the vaccine if possible and take significant precautions if not. But the only absolute deterrent is a history of severe allergies to a previous dose—a common-sense one. “If you had a serious reaction to an mRNA vaccine, you should think twice before getting another,” Levy says.

Otherwise, the evidence does not support any general safety concerns. “What often gets lost in the conversation is just how safe these vaccines have proven to be,” Faust says. The primary series clinical trials enrolled tens of thousands of participants—massive studies that helped establish a strong safety profile early on. “The risk of serious side effects was always low—and it’s only gotten lower,” he continues.

When are updated vaccines coming out?

In August or September, pharmaceutical companies will update the precise composition of the Covid-19 and flu vaccines, following recommendations from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The goal is to match the circulating strains as closely as possible, Levy says.

For the upcoming season, the FDA has recommended a vaccine targeting the LP.8.1 strain, a close cousin of last year’s strain—both variants belonging to the same lineage. “So there’s no big change in the makeup of Covid-19 vaccines,” Fiscus says.

While year-to-year changes may seem marginal, Faust explains that they’re part of a cumulative process to keep up with this ever-changing virus. So while the decision to get an updated vaccine will depend on individual factors, staying current remains a reasonable strategy.

If the new recommendations don’t include me, can I still get the updated Covid-19 vaccine?

You will still likely be able to receive the updated vaccine, but it might cost you.

After all, the guidelines explicitly allow for shared decision-making. “It doesn’t mean you can’t prescribe things just because there’s not an FDA indication; it means you’ll talk to your doctor,” Makam says—and decide if the vaccine is appropriate and should be given.

The issue is that, with this shift away from universal recommendations, insurance coverage becomes less certain. Per the Affordable Care Act, if the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends a vaccine, then private insurers have to cover it. But without a federal recommendation and now without a committee to advise one, vaccine access may fall into financial limbo. “You could end up with a scenario where it’s technically possible to get immunized, but there are administrative and financial barriers to doing so,” Levy says.

And that cost burden will fall unevenly, with potential costs varying based on an individual’s insurance plan. “If you’re going to have to pay out of pocket—$10, $20, $50, $100—that might be enough to sway people who were on the fence,” Makam says.

Thus, whether a vaccine is officially recommended can influence whether it’s covered—so even if a doctor advises it, patients might still have to pay on their own dime. In other words, tied up with the question of who should get vaccinated is the more fundamental concern of who can. For shared decision making and individual choice to be meaningful, Levy says, vaccines should still remain accessible to patients in the absence of universal recommendations. “The appropriate solution is not mandates,” he adds, “but availability.”