Author: John Murphy Affiliation: COVID-19 Long-haul Foundation

🌬️ Introduction: When Breathing Doesn’t Bounce Back

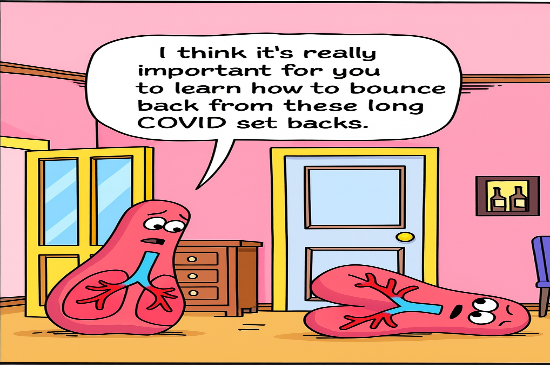

For many people recovering from COVID-19, the virus doesn’t simply go away. Weeks or months later, they find themselves struggling to catch their breath—sometimes after climbing stairs, sometimes just sitting still. This lingering symptom, known as dyspnea, is one of the most common and distressing features of Long COVID.

In this article, we explore why shortness of breath persists in Long COVID, what’s happening inside the body, how genetics and immune responses play a role, and what treatments are showing promise. We also highlight major studies and ongoing research efforts that are helping us understand—and hopefully resolve—this condition.

📊 Epidemiology: How Common Is It?

Shortness of breath affects 26% to 56% of people with Long COVID, depending on the study and population. A 2024 Australian cohort study found that over half of long-haulers still experienced breathlessness six months after infection.

Key Risk Factors:

- Severe initial COVID-19 illness

- Hospitalization or ICU stay

- Female sex

- Pre-existing lung or heart conditions

🔬 What Causes It? The Multiple Layers of Dyspnea

There’s no single cause of post-COVID breathlessness. Instead, it’s a multifactorial syndrome involving lungs, blood vessels, nerves, and the immune system.

1. Lung Damage and Fibrosis

COVID-19 can injure the tiny air sacs in the lungs (alveoli), leading to scarring or fibrosis. This makes the lungs stiff and less able to expand, reducing oxygen exchange. Studies from Stanford and the NIH show elevated levels of TGF-β1 and MMP9, which drive this scarring process.

2. Microvascular Injury

COVID-19 damages the lining of blood vessels, causing tiny clots and poor oxygen delivery. Elevated D-dimer and von Willebrand factor levels are common in long-haulers.

3. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction

Some patients develop POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) or vagus nerve dysfunction, which affects breathing rhythm and heart rate—even when lungs are structurally normal.

4. Ongoing Inflammation

Even months after infection, many patients show elevated IL-6, TNF-α, and interferon levels. This chronic immune activation can affect lung tissue and breathing control.

🧬 Genomic and Molecular Clues

Genetic studies are helping us understand why some people develop persistent dyspnea while others recover quickly.

🧪 GWAS Findings

A 2025 genome-wide association study identified two key regions:

- Chromosome 3p21.31: Includes genes like CCR9 and SLC6A20, linked to immune signaling and lung function.

- Chromosome 6p21.32: Contains HLA-DQA1, associated with autoimmune responses.

🧬 Transcriptomic Signatures

Biopsies and blood samples show increased expression of:

- COL1A1 (collagen production)

- TGF-β1 (fibrosis driver)

- MMP9 (tissue remodeling enzyme)

These genes suggest that fibrotic remodeling is a major contributor to breathlessness.

🧠 Mechanisms of Action: What’s Actually Happening?

🦠 Viral Persistence

Fragments of SARS-CoV-2 RNA have been found in lung tissue months after infection, suggesting the virus may continue to provoke inflammation.

🧫 Fibrotic Remodeling

Fibroblasts (scar-producing cells) become overactive, stiffening lung tissue and reducing elasticity.

🧠 Neuroimmune Crosstalk

Inflammation in the brainstem and vagus nerve may alter how the body perceives breathlessness—even when oxygen levels are normal.

🩺 Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Common Symptoms:

- Breathlessness during exertion or rest

- Chest tightness

- Fatigue and dizziness

- Rapid heartbeat or palpitations

Diagnostic Tools:

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): Measure lung capacity and airflow

- High-Resolution CT (HRCT): Detects fibrosis and scarring

- Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET): Assesses oxygen use during activity

- Blood Tests: CRP, IL-6, D-dimer, ferritin

💊 Treatment Options: What’s Working?

🧘 Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Structured breathing exercises and physical therapy improve lung function and stamina. Programs often include:

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Pursed-lip breathing

- Gentle aerobic activity

💉 Corticosteroids

Used to reduce inflammation and slow fibrosis:

- Prednisone: Moderate potency, tapered over weeks

- Dexamethasone: High potency, used for acute flares

🧪 Antifibrotic Drugs

- Nintedanib and pirfenidone are being tested for post-COVID lung fibrosis. Early results show promise in slowing scarring.

🧬 Biologics

- Nintedanib (IL-6 blocker) and baricitinib (JAK inhibitor) may help modulate immune overactivation.

🔍 Ongoing Research

🧠 NIH RECOVER Initiative

A $1.15 billion program studying Long COVID across organ systems. Includes pulmonary imaging, genomics, and symptom tracking.

🌍 International GWAS Consortium

24 studies across 16 countries are mapping genetic risk factors for Long COVID symptoms, including dyspnea.

🧪 Stanford Pulmonary Fibrosis Trials

Investigating antifibrotic therapies and immune modulators in long-haulers with persistent breathlessness.

🧭 Conclusion: A Complex Puzzle, Slowly Coming Together

Shortness of breath in Long COVID is not just a lingering symptom—it’s a sign of deeper biological disruption. From lung scarring and blood vessel damage to immune dysregulation and nervous system imbalance, dyspnea reflects a multi-system challenge.

But thanks to genomic research, imaging advances, and targeted therapies, we’re beginning to understand—and treat—this condition more effectively. Continued investment in research and patient-centered care will be key to helping millions breathe easier again.