Authors: John Murphy, M.D., MPH, DPH. ,Affiliations: President COVID-19 Long-haul Foundation

Abstract: 250 words

Abstract

Background

SARS-CoV-2 infection produces multisystem disease with prominent epithelial involvement extending beyond the respiratory tract. Increasing evidence implicates epithelial injury in both acute COVID-19 and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).

Methods

We reviewed peer-reviewed clinical, molecular, genomic, and histopathologic studies addressing SARS-CoV-2 interactions with epithelial tissues, including epidermal, dermal, mucosal, and extracellular matrix compartments.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 infects epithelial cells via ACE2 and host proteases expressed across respiratory and cutaneous tissues. Viral replication disrupts epithelial barrier integrity, alters keratinocyte differentiation, and induces innate immune activation. Endothelial–epithelial cross-talk and complement-mediated microvascular injury amplify epithelial and matrix damage. In PASC, persistent epithelial inflammation, dysregulated repair, and extracellular matrix remodeling contribute to chronic dermatologic and mucocutaneous manifestations. Therapeutic approaches remain empiric, with partial responses reported in observational cohorts.

Conclusions

Epithelial injury represents a central pathophysiologic feature of COVID-19 and long COVID. Targeted investigation of epithelial mechanisms is essential to improve treatment and reduce long-term morbidity.

Introduction

COVID-19 was initially conceptualized as an acute viral pneumonia. Subsequent clinical, histopathologic, and molecular observations have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 is a systemic pathogen with pronounced effects on epithelial tissues.¹ Epithelial cells serve as barrier structures, immunologic sensors, and regulators of tissue homeostasis. Disruption of these functions produces local pathology and systemic consequences.

Cutaneous and mucocutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 were reported early in the pandemic and span inflammatory, vasculopathic, and dysautonomic phenotypes.² The persistence of epithelial symptoms in PASC suggests durable alterations in epithelial biology rather than transient inflammatory responses.³

This review examines the etiology, viral genomics, epithelial physiology, tissue pathology, clinical manifestations, and therapeutic responses associated with SARS-CoV-2–mediated epithelial injury, with emphasis on dermal, epidermal, and matrix involvement.

Etiology and Epithelial Tropism

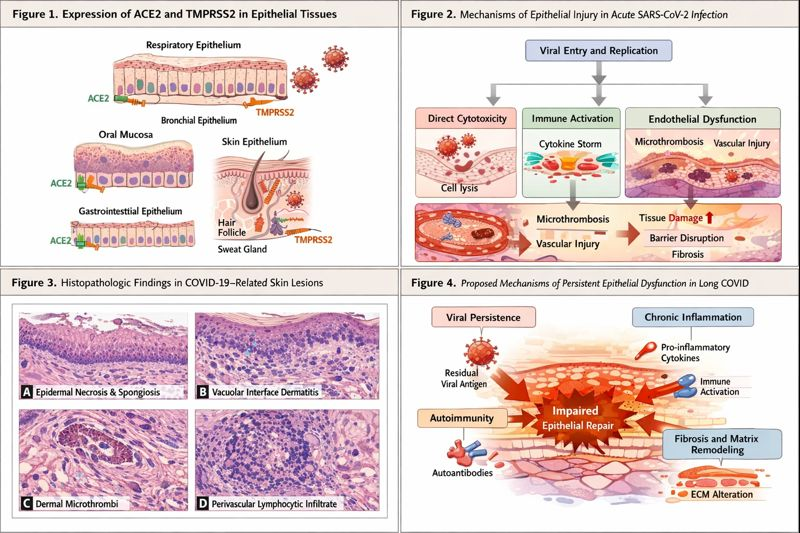

Viral Entry and Tissue Distribution

SARS-CoV-2 enters host cells through binding of the viral spike glycoprotein to ACE2, followed by proteolytic activation by TMPRSS2 and related proteases.⁴ ACE2 expression has been demonstrated in keratinocytes, basal epithelial cells, eccrine glands, and hair follicle epithelium, establishing biologic plausibility for direct epithelial infection.⁵,⁶

Although respiratory epithelium remains the dominant site of viral replication, detection of viral RNA and protein in skin biopsies suggests either direct infection or secondary involvement through hematogenous dissemination and immune-mediated mechanisms.⁷

Mechanisms of Epithelial Injury

Epithelial injury occurs through four interrelated mechanisms:

- Direct viral cytotoxicity

- Innate and adaptive immune activation

- Endothelial dysfunction and microthrombosis

- Aberrant tissue repair and fibrosis

These processes converge to produce epithelial barrier failure and chronic dysfunction.

Genomics and Molecular Pathogenesis

The ~30-kb SARS-CoV-2 genome encodes nonstructural proteins that actively suppress epithelial host defenses. NSP1 inhibits host mRNA translation, impairing epithelial regeneration, while NSP6 interferes with autophagy, a critical epithelial stress-response pathway.⁸,⁹

Single-cell RNA sequencing studies demonstrate profound transcriptional reprogramming of infected epithelial cells, including dysregulation of interferon-stimulated genes, keratin expression, and junctional complexes.¹⁰ Host genetic variants affecting interferon signaling are associated with more severe epithelial injury and prolonged disease.¹¹

Emerging epigenetic studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces persistent chromatin remodeling in epithelial progenitor cells, potentially contributing to long-term alterations in differentiation and immune responsiveness.¹²

Physiology of Epithelial Barrier Disruption

Epithelial integrity depends on tight junctions, adherens junctions, and regulated turnover. SARS-CoV-2 disrupts these processes by:

- Downregulating claudins and occludins

- Inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α)

- Promoting oxidative stress

In the skin, keratinocyte activation leads to abnormal differentiation, hyperproliferation or atrophy, and impaired wound healing.¹³ Damage to adnexal epithelium contributes to alopecia and sweat dysregulation observed in post-acute disease.¹⁴

Pathology of Epidermis, Dermis, and Extracellular Matrix

Histopathologic Findings

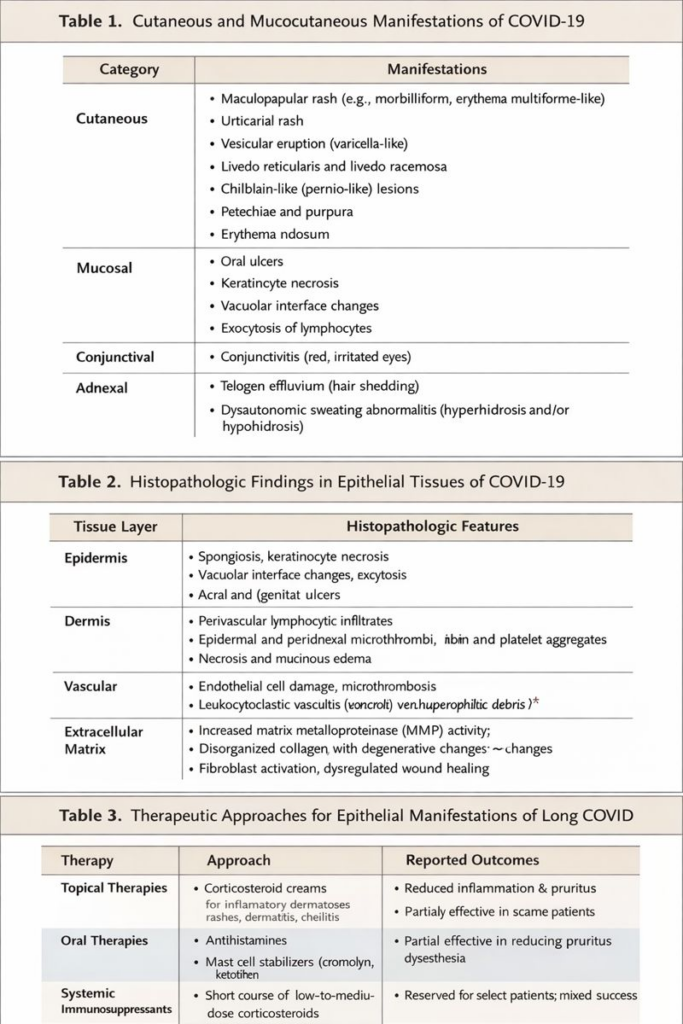

Biopsies from COVID-19–associated skin lesions demonstrate:

- Epidermal necrosis and spongiosis

- Vacuolar interface dermatitis

- Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates

- Dermal microthrombi

These findings indicate combined epithelial and vascular injury.¹⁵

Matrix Remodeling

SARS-CoV-2 infection induces fibroblast activation, increased matrix metalloproteinase activity, and collagen disorganization.¹⁶ These alterations mirror fibrotic processes observed in pulmonary tissue, suggesting shared pathogenic pathways.¹⁷

Clinical Manifestations

Cutaneous manifestations include maculopapular eruptions, urticaria, vesicular lesions, livedo reticularis, and chilblain-like lesions.¹⁸ Mucocutaneous findings include oral ulcers, glossitis, conjunctivitis, and cheilitis.

In PASC, patients report chronic pruritus, dysesthesia, hair loss, episodic inflammatory rashes, delayed epithelial healing, and persistent mucosal irritation.¹⁹

Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

PASC affects approximately 10–30% of infected individuals.²⁰ Persistent epithelial abnormalities may reflect viral persistence, autoimmunity, or maladaptive repair. Skin biopsies from long-haul patients demonstrate chronic inflammatory infiltrates and altered keratinocyte gene expression months after infection.²¹

Therapeutic Interventions and Outcomes

Acute Phase

Management of epithelial manifestations during acute COVID-19 is supportive. Topical corticosteroids, antihistamines, and emollients are commonly used. Systemic corticosteroids are reserved for severe inflammatory disease.²² Early antiviral therapy reduces viral burden.²³

Long COVID

There is no standardized therapy for epithelial manifestations of PASC. Interventions include:

- Topical and systemic anti-inflammatory agents

- Antihistamines and mast-cell stabilizers

- Short courses of systemic corticosteroids

- Dermatologic rehabilitation

Observational studies report partial improvement in 40–60% of patients.²⁴

Discussion

Epithelial injury represents a unifying feature of acute and chronic COVID-19. Persistent epithelial dysfunction may underlie symptom chronicity, impaired tissue repair, and reduced quality of life. The absence of targeted therapies reflects limited mechanistic insight and a paucity of randomized trials.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 causes direct and indirect injury to epithelial tissues across multiple organ systems. Recognition of epithelial pathology as a core feature of COVID-19 and PASC is essential for therapeutic development.

Figures

Figure 1. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression across epithelial tissues.

Figure 2. Mechanisms of epithelial injury in acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 3. Histopathologic features of COVID-19–associated skin lesions.

Figure 4. Proposed mechanisms of persistent epithelial dysfunction in PASC.

Tables

Table 1. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.

Table 2. Histopathologic findings in epithelial tissues.

Table 3. Therapeutic approaches in epithelial PASC and reported outcomes.

Supplementary Appendix

Supplementary Methods: Search strategy and inclusion criteria.

Supplementary Table S1: Cohort studies of cutaneous COVID-19.

Supplementary Table S2: Long-COVID treatment regimens.

Supplementary Figure S1: Single-cell transcriptomic alterations.

References

- Ackermann M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128.

- Galván Casas C, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71–77.

- Sudre CH, et al. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–631.

- Hoffmann M, et al. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.

- Sungnak W, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26:681–687.

- Hamming I, et al. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637.

- Colmenero I, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:729–737.

- Thoms M, et al. Science. 2020;369:1249–1255.

- Cottam EM, et al. Autophagy. 2014;10:1440–1455.

- Muus C, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:1207–1217.

- Zhang Q, et al. Science. 2020;370:eabd4570.

- Minnoye L, et al. Cell. 2021;184:5739–5757.

- Freeman EE, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1116–1127.

- Starace M, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e175–e177.

- Magro C, et al. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13.

- Wynn TA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–537.

- George PM, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:807–815.

- McMahon DE, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1–11.

- Davis HE, et al. Lancet. 2023;401:130–142.

- Nalbandian A, et al. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615.

- Swank Z, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:e150–e157.

- Freeman EE, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1116–1127.

- Beigel JH, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–1826.

- Davis HE, et al. Lancet. 2023;401:130–142.