Authors: Nancy Lapid February 3, 2021

COVID-19 attacks the pancreas

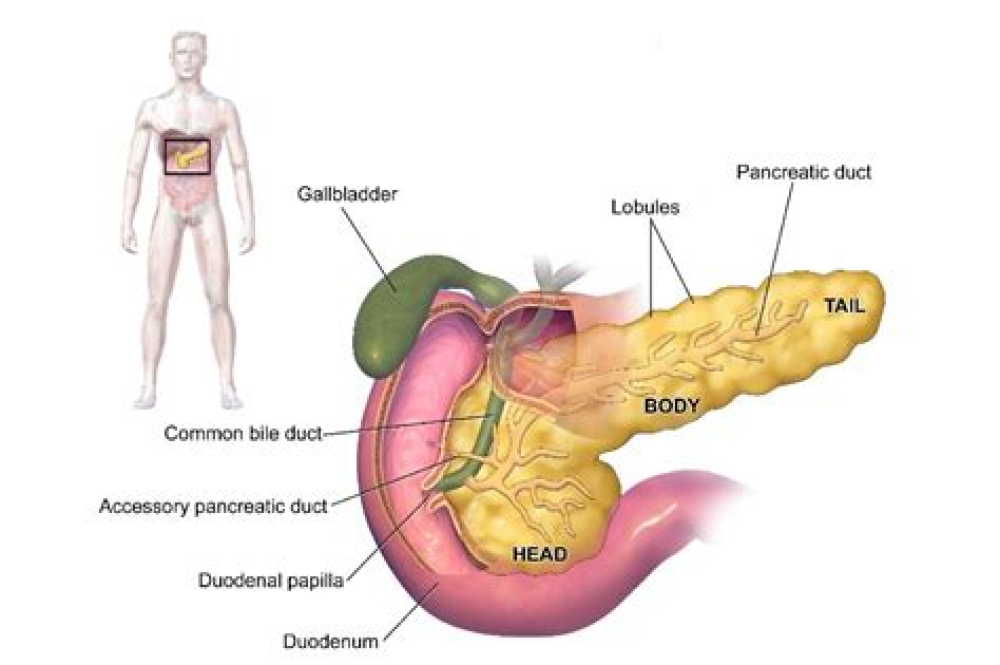

The new coronavirus directly targets the pancreas, infecting and damaging its insulin producing cells, according to a new study. The findings may help explain why blood sugar problems develop in many COVID-19 patients, and why there have been reports of diabetes developing as a result of the virus. The pancreas has two jobs: production of enzymes important to digestion, and creation and release of the hormones insulin and glucagon that regulate blood sugar levels. In a paper published on Wednesday in Nature Metabolism, researchers report that lab and autopsy studies show the new coronavirus infects pancreas cells involved in these processes and changes their shape, disturbs their genes, and impairs their function. The new data “identify the human pancreas as a target of SARS-CoV-2 infection and suggest that beta-cell infection could contribute to the metabolic dysregulation observed in patients with COVID-19,” the authors conclude. (https://go.nature.com/36Cmtfy)

One vaccine dose might be enough for COVID-19 survivors

COVID-19 survivors might only need one shot of the new vaccines from Moderna Inc and Pfizer/BioNTech, instead of the usual two doses, because their immune systems have gotten a head start on learning to recognize the virus, according to two separate reports posted this week on medRxiv ahead of peer review. In one study of 59 healthcare workers who recovered from COVID-19 and received one of the vaccines, antibody levels after the first shot were higher than levels usually seen after two doses in people without a history of COVID-19. In a separate study, researchers found that 41 COVID-19 survivors developed “high antibody titers within days of vaccination,” and those levels were 10 to 20 times higher than in uninfected, unvaccinated volunteers after just one vaccine dose. “The antibody response to the first vaccine dose in individuals with pre-existing immunity is equal to or even exceeds” levels found in uninfected individuals after the second vaccine dose, the authors of that paper said. “Changing the policy to give these individuals only one dose of vaccine would not negatively impact on their antibody titers, spare them from unnecessary pain and free up many urgently needed vaccine doses,” they said. (https://bit.ly/3je4Zv4; https://bit.ly/2YG0EYf)

Gout drug shows promise for mildly ill COVID-19 patients

Colchicine, an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat gout and other rheumatic diseases, reduced hospitalizations and deaths by more than 20% in COVID-19 patients in a large international trial. COVID-19 patients with mild illness and at least one condition that put them at high risk for complications, such as diabetes or heart disease, received either colchicine or a placebo for 30 days. Overall, the risk of hospitalization or death was statistically similar in the two groups. But among the 4,159 patients whose coronavirus infections had been diagnosed with a gold-standard PCR test, death or hospital admission occurred in 4.6% of those on colchicine versus 60% of those who got a placebo. After taking patients’ other risk factors into account, colchicine was associated with a statistically significant 25% risk reduction, the researchers reported on medRxiv ahead of peer review. Patients taking colchicine also had fewer cases of pneumonia. “Given that colchicine is inexpensive, taken by mouth, was generally safe in this study, and does not generally need lab monitoring during use, it shows potential as the first oral drug to treat COVID-19 in the outpatient setting,” the researchers said. (https://bit.ly/3oDSDgY)

Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine might work better with doses months apart

Among recipients of the COVID-19 vaccine from Oxford University and AstraZeneca, prolonging the interval between the first and second doses led to better results, researchers said in a paper posted on Monday ahead of peer-review by The Lancet on its preprint site. For volunteers aged 18 to 55, vaccine efficacy was 82.4% with 12 or more weeks between doses, compared to 54.9% when the booster was given within 6 weeks after the first dose. The longest interval between doses given to older volunteers was 8 weeks, so there were no data for the efficacy of a 12-week dosing gap in that group. Europe’s medicine regulator has said there is not enough data to determine how well the vaccine will work in people over 55. Given their findings, the authors say “a second dose given after a three-month period is an effective strategy … and may be the optimal for rollout of a pandemic vaccine when supplies are limited in the short term.”